I recognize myself in a current TV commercial. The ad, selling car insurance, is a spoof on persons of a certain age – definitely not avant-garde! – who are reluctant to get rid of an old phone that, though superannuated, still works. What, need to buy another? What for? Well, include me. And if I hear recently that my clunker of a phone has been programmed to slow with time – so much the better. I have slowed too.

I expect that eventually I’ll drop my phone, perhaps in the bath – a sure killer of phones in my experience – or parts will be scarce, or my digital assistant will give herself up to electronic decrepitude.

I have to acknowledge that I’m a Luddite, resistant to change. But just as old Ned Ludd and his confrères went about smashing spinning wheels, concerned that their livelihood would disappear, I’m worried too. I’m worried that in a vague, hyperkinetic way, like watching The Matrix on fast forward, we will all soon disappear in a jumble of selfies and crackerjack apps that do most anything.

I’ve renamed the digital assistant that came with my phone. I call her Methuselah, for she, too, has wearied. I’ve asked Methuselah why, for example, can one multiply negative numbers and end up with positive ones. I’ve asked philosophical questions: when is enough really enough, for Pete’s sake? And I’ve asked her how to really escape from social media. Bright as Methuselah used to be, she’s awash here.

Lately, I’ve been hearing of increasing concern with phones and school children and my ears perk up. Research suggests that adolescent mental health issues, particularly anxiety and depression, correlate with electronic device usage. Our kids’ senses of self-worth seem hopelessly entangled with social media at tumultuous stages of the life cycle, when they are especially vulnerable.

The average age at which a child gets his or her phone is around 10, but climbs from there, until 85% of kids have them by Grade 11. Once Johnny or Julie gets a phone and an appetite for social media, there’s no stopping. It may be no wonder that Sean Parker, former Facebook president, has acknowledged his site is designed to hook users, adding, “God knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

There are clues. Research by Jean Twenge and co-authors concludes that there is a “clear pattern linking screen activities with higher levels of depressive symptoms/suicide related outcomes and non-screen activities with lower levels.”

People may finally be listening. Recently JANA Partners investor group and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, who together own US $2 billion in Apple stock, penned an open letter urging Apple to convene and work with an expert panel, trying to understand how their products affect children.

While a number of societies such as the Canadian Pediatric Society urge limits on kids’ cell phone use, France has gone a step further, passing a law that will go into effect this year, banning the use of smartphones in elementary and middle schools this fall. As well – concerning adults this time – it will allow French workers to ignore after hours email.

I’m glad to see concern for kids, but happy that adults are included too. The same worries we have regarding children should relate to adults, too. They face the same issues. Chamath Palihapitiya, former Facebook vice president, advises taking breaks from social media, which he accuses of “ripping apart” the social fabric. He explains: “The short-term dopamine driven feedback loops … are destroying how society works.” And further, “There is no civil discourse, no cooperation, (only) misinformation, mistruth.”

There are an estimated 2 billion smartphones worldwide; over 75% of Canadians have them. Usage is surprising, with typical users addressing their devices around 150 times per day, which works out to three to five hours per day, or perhaps seven years of our lives. These little helpers are addictive. They run into family time, disrupt work-life schedules and hamper productivity. Some suggest, for instance, that it takes about 25 minutes to get back on task after a phone interruption.

Some say our zombie-like involvement with our machines harks back to our evolution. We’re hard-wired, evidently, to attend to new stuff, the so-called novelty bias. A new ping or bleep or beep is something we just can't ignore. But we’re also creatures of habit. The influence of variable rewards was mapped out by B.F. Skinner with white Carneaux pigeons. Skinner varied dispensing food, available to the birds pecking at Plexiglas, and under these unstable conditions, the birds went crazy. One pigeon tapped the Plexiglas 2.5 times per second for 16 hours. Another tapped 87,000 times over 14 hours, even though it was rewarded less than 1% of the time.

In analogous fashion, three of four email messages or social media alerts may well be droll or uninteresting, but a fourth will be juicy and novel, so it will harden our near-automatic responses to attend and re-attend to our devices.

The truth is that we all have weak attention filters and the purveyors of our gadgets and their software have become “virtuosos of persuasion.” The business model involved is simple enough: the more time one stays connected, the more revenue. I relate our hyperbolic connectedness to lives that are increasingly insecure as we withdraw from engaging with our communities and, indeed, with the marrow of ourselves. Ours is an era characterized by alienation, distraction and loneliness. As I write this, the United Kingdom has named its first Minister of Loneliness, in stark contrast to the burgeoning numbers of us stalking the planet.

Some argue that all this technology has proven to be no big deal in the past, that we’ve been dealing with it forever. Socrates, for instance, worried that writing would create forgetfulness as memorization became less important. There were similar concerns with the advent of printing presses, radio, television and so forth: the world, it was argued, was heading for hell in a handbasket.

This time may be different, since it’s all encompassing. “Technological determinism” contends that a society’s technology determines its cultural values, its social structure, and, ultimately, its history. We’re living out Moore’s Law, for instance – the number of chips on an integrated circuit doubles at short, regular intervals of from 12 to 18 months. This doubling of our capabilities has totally revamped our lives, and there’s more to come.

We are carried along, mostly blind to our new technologies. They just happen. And one day when the freezer door is talking to me, and a drone delivers my pre-, pro- and post-biotics, I’ll probably not remember that I had a choice in the matter at all.

In the meantime there’s lots of talk about AI, or artificial intelligence. As the digital world prevails, experts predict that man-made super-intelligence will come into play. Nick Bostrom, a Swedish philosopher at the University of Oxford paints a disturbing scenario: if humans create a superior machine that is able to learn at will, it may come to dominate us and forever change the world.

I can follow Bostrom and colleagues well enough, but I don’t think we need to think in outlandish sci-fi terms, as if we lived in a Marvel comic book. Technology’s triumph has already happened, noiselessly and without our notice. I’m ready to run up the white flag and proclaim tech’s victory, our loss.

What then will I do about my smartphone?

Well, I’ve decided to keep it. I’m thinking about the long haul. Should I persist another decade, I expect there will be 10 or 15 models that are newer than mine. I will have a genuine collectible on my hands.

I plan to bundle it up with my old Commodore computer, a slide rule from university days and my old in-car record player. I’m going to sell it all.

Not for about 10 years, though.

I’ll be ready then.

References available upon request

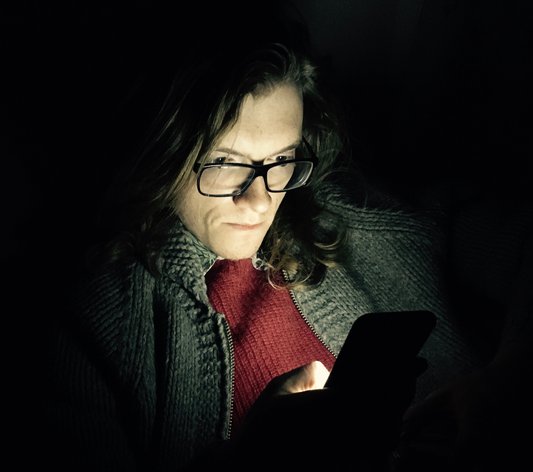

Banner photo credit: Jordan Mcqueen, unsplash.com

- Emerging Leaders in Health Promotion ventures outside of mental and physical boundaries

- Alberta Blue Cross is going for gold with the AMA Youth Run Club

- 10 reasons to use MyHealth.Alberta.ca

- Can the Health Information Act prevent physicians from using Netcare to respond to patients’ complaints?

- And 6 more articles in