Construction of the prominent Cancer Research Centre on the 16th Avenue NW Calgary Foothills Hospital site will bring the range of health care services and facilities in Calgary one step closer to those in Edmonton. Long considered, it will provide a cancer research facility in Calgary, similar to the one named after Dr. W.W. Cross in Edmonton, now called the Cross Cancer Institute.

With it comes the opportunity to name the research centre. Should it be named after a major donor, a physician, a non-physician, or nobody at all? There are compelling reasons to name it after pioneer Calgary cancer surgeon, Dr. John S. McEachern.

But that suggestion faces headwinds.

High-profile facilities have increasingly followed the American approach of acknowledging major donors. Even more aggressive have been hockey arena owners, who rent the names on their facilities for shorter and shorter periods at higher and higher prices.

Who was Dr. McEachern? He was a far-sighted, ethical, articulate and persuasive 1897 University of Toronto gold medalist. He came to Calgary after a year of surgical studies in England, having concluded it was the best North American opportunity for him. Arriving in 1905, he began the McEachern Clinic, which consisted of six to eight specialists and operated until 1978.

Dr. McEachern came to medical prominence as the third president of the Alberta Medical Association in 1908-09, and the first from Calgary. A strong Canadian Medical Association proponent, he successfully proposed, as a committee of one, the financial recovery plan to turn around the nearly bankrupt CMA after WW I.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recognized his competence by granting him a fellowship (FACS) in 1919. Five years later, he was the second vice-president of the ACS under president, Dr. Charles Mayo.

Even before the Great Depression, Dr. McEachern understood the importance of improving access to medical care and the need for a comprehensive health insurance program.

Joining the CMA’s committee on economics in 1931, McEachern became the link with the AMA that developed the first set of principles and coverage for a provincial health insurance program, in its proposal to Alberta’s Hoadley Commission in 1932.

The CMA’s principles were approved during McEachern’s presidential year in 1934-35. That same year, American physicians rejected any government involvement in health insurance, leaving it to the private sector to provide for the patient, while the CMA accepted that the federal government had a responsibility to pay for those who could not afford it.

To prepare for the national discussions that would follow, Dr. McEachern secured AMA approval to legally join or federate with the CMA in 1937. All provincial associations followed the Alberta lead in 1938. In 1943 the CMA, now representing all Canadian physicians, formally supported a national health insurance plan, in a 78-0 vote.

But it was the CMA’s cancer initiative that became Dr. McEachern’s most singular achievement. It began with radiologist Dr. W. Herbert McGuffin and Deputy Minister, Dr. Malcolm R. Bow and the formation of the AMA’s cancer committee in 1931. They made cancer a notifiable disease to improve the accuracy of cancer statistics, and they required all hospitals over 100 beds to establish a cancer case review committee.

Through the AMA, Dr. McEachern asked the CMA to assess the value of a national cancer association. As chairman of the CMA’s 1932 cancer study group, he recommended a national committee be formed, and, if necessary, include lay members.

During his CMA presidential year, he had the opportunity to foster the 1935 King George V cancer campaign. It raised $420,000 from 320,000 donors – mostly children. As Dr. McEachern pointed out, one donor who had contributed $1,000 was of less importance than 1,000 who contributed $1 each. McEachern recognized that fundraising for cancer would be a perpetual activity. Named as the only physician on the fund’s board, he was instrumental in securing funding from it for cancer education in Canada.

After his presidential year, Dr. McEachern returned to the cancer question by presenting the recommendations of a Calgary-based nucleus committee, which secured CMA approval for a new medical/lay board in 1938. His rationale was that physicians represented only 1/10 of 1% of all Canadians, so there must be intelligent cooperation with the other 99.9%.

Dr. McEachern was elected the first and only president of the committee until he retired in 1944. He was named the Canadian Cancer Society’s first honorary life member in 1946.

After WW II, Federal Minister of Health, Paul Martin, Senior, requested the King George V Fund create a national cancer research body, which it did – the NCIC, headed by Saskatchewan researcher Dr. Allan Blair.

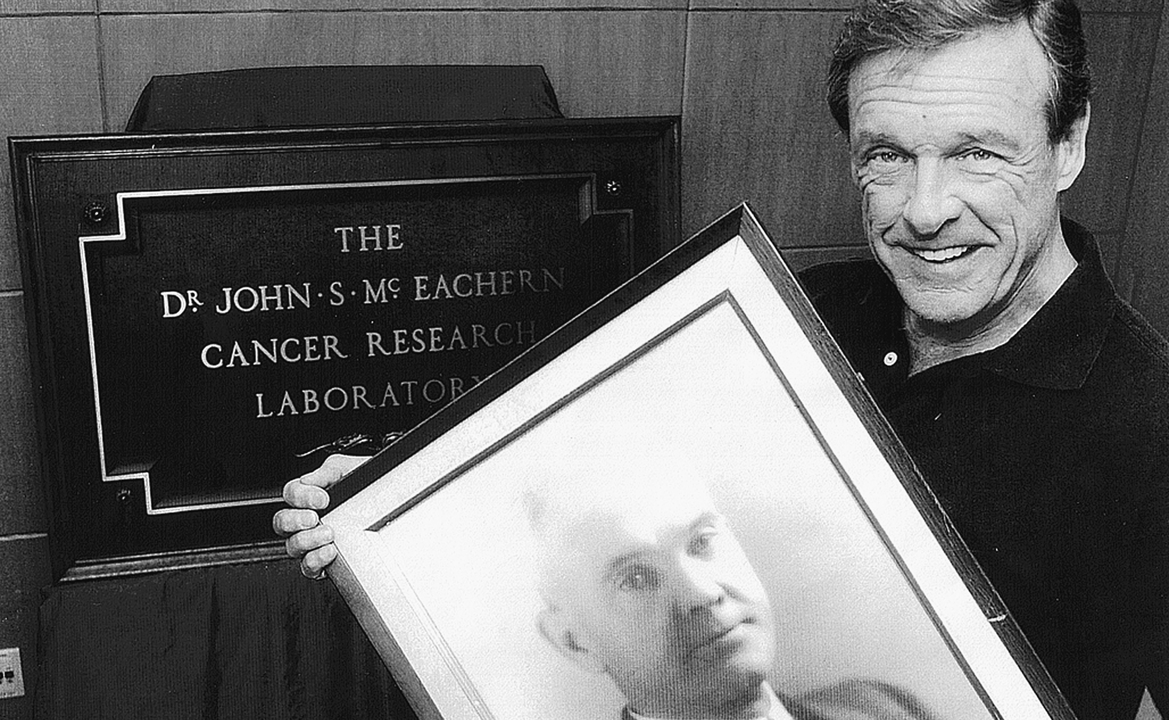

Following McEachern’s passing in 1947, the Alberta Cancer Society, with Mrs. McEachern as the honorary chairperson, raised 37% of all donations for the national society: more than any other province. A year later, Dr. Blair suggested that the next year’s fundraising proceeds be used to build a cancer research laboratory. Completed in 1952, it was named after Dr. McEachern and located in the basement of the U of A medical school. It was closed in 1996.

In 1950, the Canadian Cancer Society initiated the McEachern Memorial Cancer Research Scholarship Fund. Dr. H. E. Duggan, the future professor and head of radiology at the U of A and at the Foothills Hospital, was the first of 50 annual recipients.

Alberta is a young province and has the opportunity – nay, the responsibility – to identify, honor and recognize its influential pioneers. While there will never be a universal criterion for selecting a name – be it for schools, highways, university faculties or facilities – there are precedents in the cancer field. Of the 11 Canadian cancer centers, four are named after physicians, two after donors, three use the government’s name, one is named after a former provincial cancer leader and one after a princess.

In Alberta, the Dr. W.W. Cross name was selected because he was minister of health for 20 years (1936-56) and introduced the first free cancer care program in Canada in 1941. Dr. Tom Baker was an Edmonton teacher and president of the Alberta Cancer Board for 17 years, during the opening of the Baker Cancer Center in Calgary in 1978.

What’s in a name? Any name lasts a long time, therefore it is important to be knowledgeable and thoughtful before making a naming decision – particularly one that goes beyond its monetary value. Was/is there a relationship of significant duration between the individual and cancer care? Is there a life story worth sharing in that relationship? Does the name promote pride, respect and admiration in the organization? Does it foster cancer care and facilitate cancer education and research? Does it contribute to present and future fundraising? And in this case, does it relate to Calgary?

Dr McEachern’s contributions to medical and health care in Canada were acknowledged during his time, when the CMA gave him its highest award, the second F.N.G. Starr Award, in 1938. Only the isolators of insulin preceded him. The Canadian Medical Hall of Fame inducted him in 2006, the first Alberta clinician to be so honored.

Now is the time to acknowledge McEachern’s contributions to cancer care – and recognize the man most responsible for the development of the national organization for cancer care, education and research we have in Canada. Recognition has already been given to Dr. Cross in Edmonton.

Fortunately, with the closure of the Dr. J.S. McEachern Cancer Research Laboratory in Edmonton, his name is now available for recognition in Calgary.

Banner image: CMA Executive Committee, 1931-1932 as drawn by Dr. H. Agnew. Dr. McEachern.