The Horsemen of the Apocalypse are not finished their business yet. Dark, dismal global tidings continue: vainglorious Vlad’s Russian army lobbing bombs (from a safe distance) at Ukrainian cities and civilians with his finger fidgeting over the Iskander tactical nuclear button, the Chinese Commie Party sabre-clattering in the Taiwan Straits, inflation rising towards 9%, non-indexed taxes rising and global temperatures pushing daily highs in Europe and Britain.

Thank God our federal government is keeping us safe by randomly checking for new variants in the peregrinators entering Canada – though, of course many rapid tests do not actually turn positive until day three to four of symptoms. Is there something about the government/testing company contract that I’m not getting? Right now, the main Canadian health care problem is widespread care deficits and hospital corridor care but, of course, that’s not their problem.

Are you in need of a restorative tonic to the current dreary world news? Here’s a topic that is obliquely relevant and something I’ve been delving into recently: an antidote to folly, a salve for the soul and a healthy mental exercise – family genealogy. It’s an intriguing, enlightening and humbling exercise.

There’s a nostalgia about it; a yearning for lost contact with grandparents, aunts, uncles and times past; a curiosity to know about people who were one’s progenitors and an insight into the hard work and hardship of their lives. Without a knowledge of one’s ancestors a part of oneself is missing. Did you know that genealogy and ancestry websites are the second most visited category of internet websites? No need to mention what the top category is.

History documents only the famous; genealogy records us all. Standard history devotes too much attention to the imperious, the self-assertive, the pompous, the deluded and the attention seekers – whereas genealogy is a level field. It’s slightly comforting to know that we’ll all feature in several family trees thanks to rigorous central record keeping both on paper and digitally – the efficiency and resolve of these bureaucratic agencies in garnering information is second only to the Canada Revenue Service.

Most doctors are trained to elicit a family history at a first consultation. The American Medical Association suggests this should include first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) as well as second degree (grandparents, grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, half-siblings) and third degree (great-grandparents, great-grandchildren, great-uncles/aunts, first cousins). This part of the history should take you less than an hour at first consultation. I don’t know anyone other than a medical geneticist who has time to cover all those kindred with dates, causes of death and serious illnesses, but most try with a general question: “Any illnesses that run in the family?”

And most of us know causes and dates of death of our own first-degree relatives and a few of our second-degrees, but beyond that we depend on oral family history. But there are gaps: untimely deaths, migrations and displacements. Recording centrally on paper or digitally is best. My friend, Dr. Alex McPherson, upbraided me years ago on a delay in writing a paper on a clinical trial of BCG immunotherapy in malignant melanoma: “If it’s not written and recorded, then it doesn’t exist,” he’d say. That’s correct for modern science, but I’m not so sure about family history stories – inaccurate these may be in specific details but perhaps relevant in a general kind of way.

Anyway, I hope these intergenerational family stories contain whiffs of truth because my father used to say: “Aye, the word in Leadhills, Lanarkshire, Scotland, is that Andrew Barton Paterson was a relative.” Andrew Barton Paterson is a bit better known to the world as “Banjo Paterson” and really well-known as the author of Waltzing Matilda – the unofficial Aussie national anthem.

We’re descended from a lead, coal and gold mining family. My dad was a mining engineer who helped develop the hydraulic pit prop, an improvement on sticking thick trunks of wood from the pit’s entrance to the coal face to prevent tunnel cave-ins. He got a PhD for his work and talked at mining meetings. At gigs in Australia, he’d casually mention that a distant relative might be Andrew Barton Paterson, otherwise known as Banjo, who was the son of a Scots immigrant to Australia from Lanarkshire. This information brought a buzz of interest, and usually it was unnecessary to buy any drinks after. Banjo was a 19th-century Aussie poet, journalist and author. I’ve continued this stretching of oral family history by telling my kids about Banjo. My son named his lovely black Malamute dog Banjo. Banjo died last year and was sent over the Rainbow Bridge with full honours.

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” – Arthur Conan Doyle

So, this is decidedly not the way to start a family tree, as Conan Doyle’s quotation succinctly summarizes. You should start with yourself and work backwards, and this is where real genealogy fits in. Enter Ms Sheila Duffy, a friend from my Edinburgh University days, with whom I re-connected. Ms Duffy is a professional family genealogist consulted by interested families looking for ancestry but also by lawyers handling “intestate inventories” looking for relatives to receive the worldly proceeds of a deceased relative.

But I was determined for a quick hit: Banjo was the eldest son of a Scots immigrant from Lanarkshire, Scotland, one Andrew Bogle Paterson, likely arriving in Oz around the 1850s or 60s. His eldest son, Andrew Barton Paterson, was born in 1864. He trained as a lawyer but made his name as a journalist, war correspondent and poet – and he took the penname of "The Banjo" after his favourite horse.

His well-known works are The Man from Snowy River and Waltzing Matilda with many other poems of Aussie outback life. But the jaunty Matilda tune was actually composed by one Miss Christina MacPherson, whom Banjo met at a party at her home. He heard Christina’s tune and was inspired to write the famous lyrics. Following this super-harmonious collaboration, Banjo was suddenly asked to leave the MacPherson property, leading some to conclude that he (already betrothed to another) had engaged in a scandalous liaison with Miss MacPherson. But this is all idle rumour.

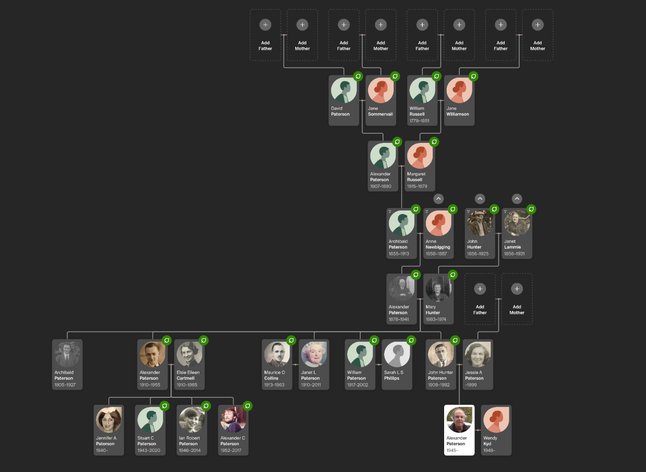

So now we’re doing it properly. I now have a family tree from the Registry Office in Edinburgh (thanks to Ms Duffy) going back to the late 1700s – all lead, gold and coal miners based in Leadhills, Scotland. But no link to Banjo! The question now is did Alexander Paterson, a great-great-grandfather born in 1807, have brothers or cousins (i.e., Andrew Bogle) who had sons who could have been Banjo’s father or grandfather? So it’s now on to “Scotlandspeople” (an ancestry website) and parish records.

But why this search for genetic connection to the famous or the celebrated? Subconscious conceit? Possible. Interest? Yes. Might some of Banjo’s dusty genes have sprinkled on my family? Yes! On me? Yes! I scrape at the violin and love Waltzing Matilda. My son plays good gypsy jazz on guitar. Maybe that thin strip of genius genes has domiciled in our DNA?

But Ms Duffy cautions against these desperate outbreaks of hope: “I always warn people (especially those who claim to be descended from Rob Roy McGregor or Bonnie Prince Charlie ... funnily enough it’s never from murderers or robbers!) that most of us are descended from non-entities.”

Non-entities? Ah well. But in some ways looking at your genealogy is a pilgrimage – a pilgrimage to the past to honour the long dead. Getting older has something to do with it – a forlorn interest in where we’re going to and the more accessible curiosity of where we’ve come from. I regret not listening to discussions of forebears by grandparents. There were much more important things to do – golf, going to a party …

Sheila also found a great-great-grandmother on my mother’s side who featured in a bigamy case at the Old Bailey in 1874 (as a witness … hmm – Ms Duffy’s comment: “In the old days it was almost impossible for working class people to divorce ... so bigamy was relatively common ... very rare now because divorce is so easy”.) She also found the passenger ship’s manifest of the SS Caledonia leaving Glasgow in 1909 for the USA with my paternal grandparents and their children on board.

These preliminary finds are not as harrowing as those uncovered for American celebrities on Henry Louis Gates’ PBS show Finding Your Roots with his extended staff of assistant researchers. They expose hidden facts about the ancestors which often stun and can be highly emotional. Our ancestors were secretive about the unpleasant aspects, the shameful events and the bitter hardships of their lives.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were times of great social change with relevance for many immigrants to Canada. Recall that scene from the BBC show Upstairs Downstairs where Lord Bellamy accidentally meets Hudson, his butler (played by Gordon Jackson) dining (finely dressed) in a top London restaurant with his visiting brother, a successful engineer back from Africa having built important bridges on the Zambezi. Hudson has told his brother he “works for an MP” avoiding the truth that he was a butler and “in service.” His Lordship chats amicably with the brother pretty much as equals while the embarrassed Hudson miserably bows and scrapes to his employer much to his brother’s surprise and His Lordship’s amusement.

This scene illustrated the rigid class system of the early 1900s which was splintering through the power of education and merit-based success. Many families experienced this, my own included, with the often self-educated, smart brother emigrating to Canada, Australia or the USA and thriving, but leaving behind siblings stuck in the old ways.

When I visited Leadhills, Lanarkshire, as a boy from our big house in Edinburgh and saw the rows of miner’s cottages and met the poor relations who had stayed behind earning a fortune for the Earl of Hopetoun, it was a poignant lesson of the power and importance of education and ambition.

In Canada, many immigrants and Indigenous people have Scots, Irish or English names (e.g., Ms RoseAnn Archibald, current Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.) It’s salutary for all to explore their ancestry. Those with Canadian ancestors could have several ethnic backgrounds – Indigenous, French, English, Acadian, Scots, Irish, Ukrainian and others.

There are many self-instruction videos on Ancestry and useful websites such as MyHeritage and the Government of Canada website: Genealogy and family history

So why not give genealogy a go? Get to it! You might find stuff you really didn’t want to know, but it adds to personal development and even a kind of liberation. It’s satisfying to connect with your ancestors and mull over their lives, achievements and failings. And it reminds us of the mixing of our genes and the rise (and fall) of status and wealth in all families.