It goes without saying that 2020 has brought unprecedented challenges for us all. As a physician, I have seen our health care systems – both within my community of Blood Tribe and within Alberta Health Services (AHS) – strain, pivot, and innovate at an incredible rate to meet the changing needs of our patients. Looking back at the last eight months teaches us a lot about the resiliency of Indigenous peoples and the innovations that have been put into action. We have also seen the strength of partnerships between Indigenous communities and AHS.

Building on the lessons learned (so far), in July 2020, AHS’ Indigenous Health Program and the Indigenous Health Strategic Clinical Network were brought together to form the Indigenous Wellness Core (IWC), where I have humbly agreed to serve as the Senior Medical Director. My leadership team colleagues include Val Austen-Wiebe as the Senior Program Officer and Marty Landrie as the Executive Director.

The concept of the IWC came, in part, from the recent adoption of the AHS Indigenous Health Strategy (IHS). The IHS’s purpose is to guide the development of structures, processes and an organizational culture with a vision of achieving health equity for Indigenous people in Alberta. While it is the responsibility of all programs and zones to undertake work on Indigenous health, leadership recognized that the strategy required a dedicated group to drive implementation and ensure accountability. At a high level, the IWC:

- Brings alignment and creates efficiencies in Indigenous health under one umbrella department.

- Establishes a distinct home for Indigenous health to better implement the Indigenous Health Strategy.

- Works in collaboration and partnerships across AHS and with all external partners toward health equity for Indigenous peoples and communities.

As Indigenous people, we know that words matter. As such, we spent a significant amount of time determining our group’s name, which was informed by valuable discussions with AHS’ Wisdom Council, comprising Indigenous members who provide guidance on Indigenous health from across the health zones. We wanted our new entity to support the mental, spiritual, physical, and emotional aspects of Indigenous health. We also understood the need to attend to the social determinants of health.

With this in mind, we have forgone the word “health” for the more holistic term “wellness.” The Wisdom Council felt very strongly about the word “core.” They shared that the notion of a “core” resonates with many Indigenous cultures who view Mother Earth as the core of identity and the source of health and holistic wellness. For Indigenous peoples, drumming represents the heartbeat at the core of all living things. The term “core” can also be understood as the center, holding the seeds that will be planted to achieve a better future. This name represents our mission to build a place that supports Indigenous wellness, connectedness, innovation, and vision into the future. Thus, the Indigenous Wellness Core was born.

Innovations continue

Though it is yet early days, there are a number of priority areas that have emerged to guide our work. These include mental wellness and substance use, primary health care, patient concerns and experiences, and cultural safety. Community capacity building underlies all of these areas of work. Much good work is underway, and we will continue to find opportunities to innovate.

ECHO+ in Indigenous communities

One major piece of work the IWC team has been leading is expanding the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model to Indigenous communities. AHS adopted the ECHO+ ”hub and spoke” model for STBBI (sexually transmitted and blood-borne infection) screening and treatment three years ago to support primary care providers using telehealth for rural, remote and Indigenous communities. Our ECHO+ team consists of a community integration coordinator and two community prevention practitioners. Melissa Potestio is the Principal Investigator from our team.

The ECHO+ project has been actively holding bi-weekly ECHO+ Case Presentation video conferences with Dr. Sam Lee, hepatologist, allowing for patients to be treated for Hepatitis C without leaving their local communities. The bi-weekly calls were re-purposed for COVID-specific discussions and clinician speakers as a response to the pandemic.

The ECHO+ team, focusing on community engagement, has reached out to every Indigenous community in Alberta to offer support and access to ECHO+ as means of curing community members with Hepatitis C. If you are a health care provider working in an Indigenous community and are interested in the ECHO+ model, please reach out to our Assistant Scientific Director, Kienan Williams, at [email protected].

Alberta Indigenous Virtual Care Clinic

As a family physician, I see the impacts that lack of access to culturally safe primary health care has on our communities. Our First Nations people face a 12-year gap in life expectancy compared to non-First Nations populations.

COVID-19 has magnified inequities, but also opened the door to opportunities in virtual care, which can bridge gaps in rural areas and improve access for chronically underserved urban Indigenous populations. The Alberta Health Services Indigenous Wellness Program Clinical Alternative Relationship Plan (IWPcARP) has teamed up with Indigenous Services Canada (First Nations and Inuit Health Branch) and First Nations Technical Advisory Group Inc. (TSAG) to offer the Alberta Indigenous Virtual Care Clinic.

Conclusion

As I look back on 2020, I am filled with a rush of contradictory emotions: fear and worry about the pandemic and the vulnerability of our peoples; concern about the long-term mental and emotional impacts of the pandemic; and sadness for my community members who continue to struggle through an opioid crisis during the pandemic.

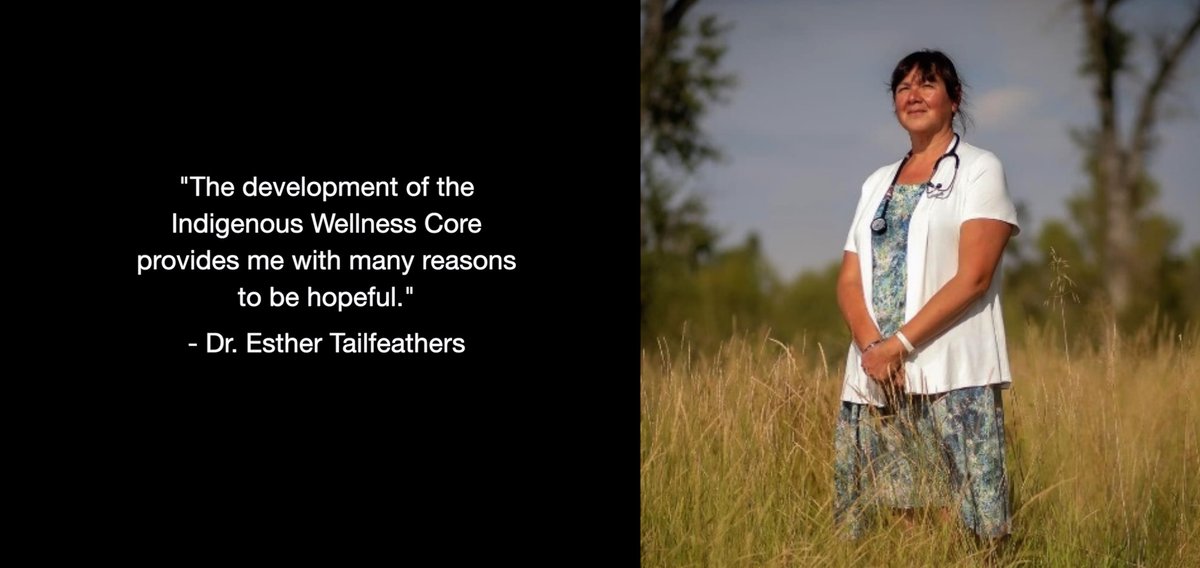

Yet despite all the challenges, 2020 has also given me many reasons to be hopeful and proud. I am very proud of the way that Indigenous communities have risen to the many challenges the pandemic has brought. I am also amazed at the way that partners have rallied around communities in this time of crisis. The development of the Indigenous Wellness Core also provides me with many reasons to be hopeful. In my many years with AHS, I can now see Indigenous health clearly enacted as an organizational priority with a structure designed to get things done!

Note from Editor: See Alberta Indigenous Virtual Care Clinic story in this issue

Banner image credit: Marvin Polis