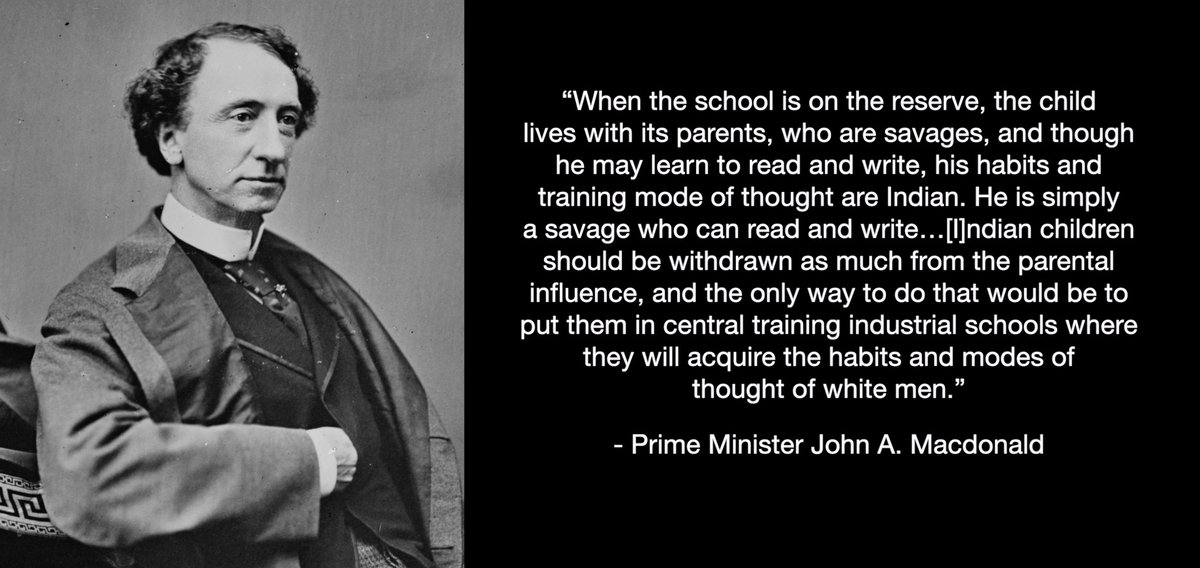

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's statement was the beginning of two things. First, Canada’s assimilation policy, which established the Indian residential school (IRS) system for Indigenous children, opening in 1883 and closing in 1996. Second, it was the foundation for systemic racism and discrimination toward Indigenous peoples within Canada. Children from ages four to 18 years were mandatorily separated from their parents, communities, and culture to attend Indian residential schools, where they were further separated by gender and age (Smith, Varcoe, Edwards, 2005).

Residential schools enforced government regulations, which included prohibiting children from speaking their language. The assumption made by both the churches and the Canadian government was that their European civilization and religion was superior to Indigenous cultures (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015). They taught the children that their Indigenous spirituality, traditional values, and beliefs were paganistic. Consequently, this created further mental and emotional separation from their families as the children looked down upon their parents, culture and communities (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996).

The legacy of residential schools, while continuing to have serious negative impact on survivors and their children, continues in the ongoing systemic racism present in many Canadian institutions, of which the justice, education and health care systems are the most significant (Richmond & Cook, 2016).

My introduction to the impacts of residential schools began in 1988, when I was asked to provide counselling services to the 600 students attending Gordon’s Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan. It was the last federally operated residential school in Canada. While there, I witnessed children identified by numbers on their personal belongings, with no toys for play or learning. Children disclosed that they were one of many generations of their families to attend residential schools.

My task was to provide individual counselling, which included teaching protective factors regarding abuse and how to identify abuse. In June 1988, a 13-year-old student disclosed to me that she was being sexually abused by the head child care worker. A formal statement was provided to the RCMP. With each statement gathered by police, another girl would disclose her sexual abuse. By early morning, there were 17 disclosures of sexual abuse inflicted upon the girls by the same staff member.

These 17 disclosures led to the first IRS staff person to be charged with sexual abuse in Canada. Similar student disclosures followed in Saskatchewan and across Canada, eventually resulting in the filing and settlement of the largest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history: the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), in 2007.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was a component of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. The mandate of the commission was to document the truth of the experiences of the former students of residential schools and to educate Canadians.

During a statement gathering process, the TRC heard the experiences of 7,000 former students and their families, including the horrific sexual, physical, emotional and spiritual abuse and inter-generational trauma they endured. Children in the Indian residential school system were subjected to unimaginable abuse in efforts to destroy their identities as Indigenous people.

The documented student experiences included: withheld food; food of little or no nutritional value; subjection to experiments without consent or knowledge of parents or the children; poor health care when they were sick with infectious diseases that were exacerbated by the overcrowded conditions in most schools; and separation from their families that prevented the sharing and teaching of cultural values and importantly, learning and valuing themselves as Indigenous persons.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR - University of Manitoba, 2015) found records of 5,000 children who never returned home to their parents. Instead, they went missing from the residential schools, and still others died due to infectious diseases, suicides and accidents.

In alignment with the Canadian government’s assimilation policy, the government established segregated Indian hospitals. One Indian hospital was Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton, opened in 1946 and closed in 1996 (Lux, 2016). Like residential schools, the Indian hospitals were underfunded, understaffed, and Indigenous people were forced to attend. Indigenous patients were sent to Indian hospitals from residential schools, from northern Canada, and from northern parts of the prairie provinces. Charles Camsell Hospital was the site of medical experimentation including forced sterilization and forced confinement for treatment of tuberculosis. There is current litigation on Indian hospitals.

The consequences of Indian residential schools to the health of Indigenous peoples have been enormously felt, evidenced by the high rates of poor mental and physical health. For instance, former IRS students misused substances to cope with their early childhood trauma and there is a high prevalence of Indigenous people with diabetes.

As they access health care, many Indigenous people are further subjected to racism, discrimination, and negative stereotypes. For instance, I was recently requested by Alberta Doctors’ Digest to seek an Indigenous person/people who would agree to share an experience with the health care system for AMA’s* Orange Shirt Day event. Unfortunately, the Indigenous people I spoke with did not have a positive experience, nor did they want to share their negative experience in fear that they would face retaliation on their next health care visit.

If you find yourself judging or stereotyping Indigenous people, reflect on where that is coming from, and what you are basing those judgments on. Do something to change your attitude and treatment of Indigenous people.

You can educate yourself on the history and the continuing inequities of the health care system for Indigenous peoples and identify ways that you can help change the system. Read the TRC Calls to Action and pick one that you can commit to and implement. And you can educate others!

In the walls of his mind from Mayproductions on Vimeo.

Resources

If you are interested in learning more about changing your relationship with Indigenous patients there are several ways you can take that positive step to reconciliation. Here are a few resources to get you started:

TRC Readings (require Dropbox access)

References

Alberta Medical Association. (2017). AMA Policy Statement on Indigenous Health

Maureen K. Lux. Separate Beds: A History of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s–1980s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

National Center for Truth and Reconciliation (2020).

Richmond, C.A.M., Cook, C. Creating conditions for Canadian aboriginal health equity: the promise of healthy public policy. Public Health Rev 37, 2 (2016).

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996). Volume 3: Gathering strength. Ottawa.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). The final report of the truth and reconciliation commission of Canada; The history, Part 1 origins to 1939. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

*The Alberta Medical Association passed a resolution in March 2016 to support the TRC Calls to Action on health, and as an organization, to support improvements in accessing quality care for Indigenous people (Alberta Medical Association, 2017).

Banner photo: All Saints Indian Residential School, Lac La Ronge, Saskatchewan. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada collection/Library and Archives Canada/PA-045174