The effect of biases and stereotypes within our health care system

Hello, my birth name is Arrow Big Smoke; my traditional name is Akwii-nee-ma-ki, meaning Pipe Woman. I am a proud Blackfoot woman and a member of the Piikani Nation. I currently work as an Indigenous Cancer Patient Nurse Navigator for Cancer Care Alberta. I am privileged and honored to work in a position where I can advocate for better treatment of my people and empower them to use their voices to get the care they should expect.

The opinions shared in this piece are inspired from my time working as a community health nurse in a First Nations community in British Columbia, my current position as an Indigenous nurse navigator within cancer care, and my time working at the Safe Consumption Site in Calgary (SCS). While working at the SCS, clients would often ask me to escort them to the closest acute care center for fear of stigmatization and being accused of seeking drugs. It is because of this trauma, inflicted on our people from biases and stereotypes within our health system, that I feel things must be done better.

As a member of the younger generation, I feel fortunate to have been born after the time of residential schools, the sixties scoop, Indian hospitals, and tuberculosis sanitoria. But regret to say that, like many, I have felt the after-effects of these events through the intergenerational trauma that government initiatives brought onto our communities and families.

My grandmother was a residential school attendee and suffered greatly after her time spent in these isolated, crowded and dilapidated buildings. She sadly passed at a young age. Others have described her to me as a kind and gentle woman. My father, a resilient, loving man, is a sixties scoop survivor, and was born in an Indian hospital.

These events have had damaging consequences in our nations. The fear and oppression have prevented our people from accessing and trusting the health care system. The history of colonialism, the boarding school system, and the treatment of First Nations during the tuberculosis epidemic greatly affected our sense of security and trust in mainstream establishments and have been identified as sources of re-traumatization for some clients.

Trail-blazers: Standing up and being heard

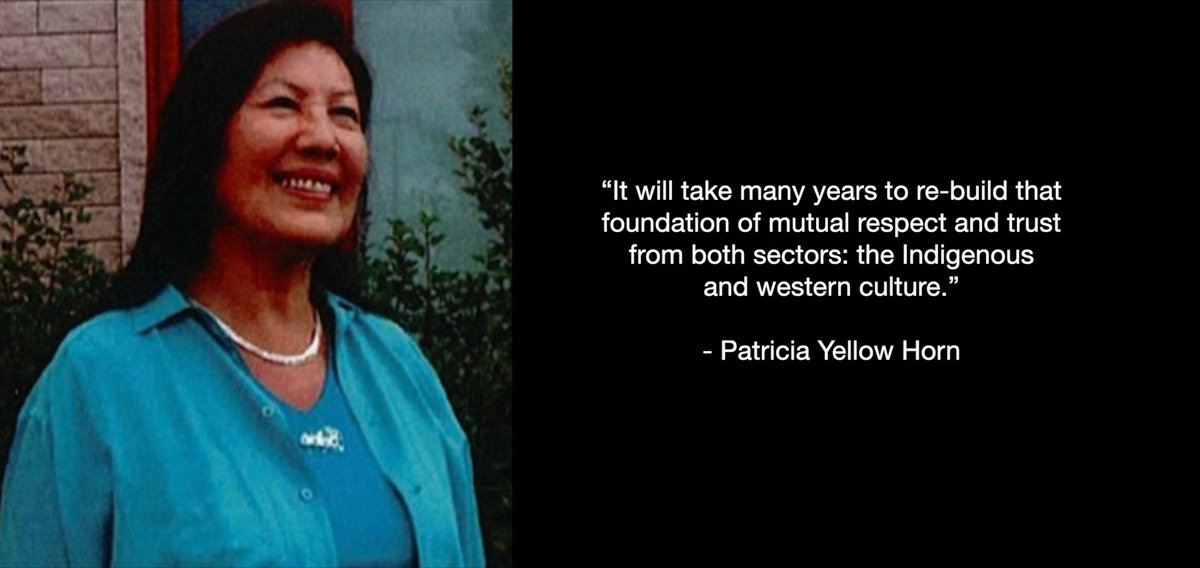

Patricia Yellow Horn, an inspiring and strong Indigenous woman, is the community health coordinator at Aakom-Kiyii Health Services. She has been a registered nurse for over 30 years and calls Piikani home. She says, “It will take many years to re-build that foundation of mutual respect and trust from both sectors: the Indigenous and western culture.”

Patricia is a strong advocate and leader within the community. Her work history includes working in women’s hospitals in the United States, and First Nations community tuberculosis departments. It is nurses like Patricia that have trail-blazed the path for younger providers like me to stand up for our people and make our voices heard.

Patricia was the inspiration behind our collaboration last spring when she recognized that cancer is a rising problem within our community. Her observation closely aligns with what the research shows. According to Horrill et al (2019, p.1) many Indigenous clients are being diagnosed with cancer at later stages and are suffering poorer prognosis. Patricia elaborates, “Many of our people want health services and care in their community, where they feel supported and understood.” This led to requesting that a cancer information session be provided to the Nation.

Taking the information out of the cancer center and to the Nation

The information session was delivered differently than how it has previously been done. Historically, if Indigenous clients wanted to engage in Western health initiatives, they would have to leave their communities, come to our health centers, and conform to rigid time schedules. With this information session, we took it to the Nation, which provided the flexibility for Nation members to access the information at their pace, without having to travel long distances. It also provided a safe environment for them to ask questions, all while being supported by their community and loved ones.

Another significant bonus was that staff from the surrounding cancer centers attended. They were able to observe a successful and proud Nation supporting each other, while dispelling fears and rumors surrounding cancer, and experiencing the culture and traditions that are often forgotten once Indigenous clients enter a sterilized hospital setting.

The attendance of staff from nearby urban cancer centers was arranged for the benefit of the Nation members, so that when they do need to attend a cancer center, they will find a recognizable, friendly face. In addition, it was a great opportunity for the health care providers to see the strength and resilience of the Piikani Nation. Too often, our nations are represented in the media and elsewhere as impoverished and resource-limited. Many outsiders do not see the unique strength that an Indigenous community possesses.

The outcome of the information session was that the Nation identified what they wanted; we listened and delivered the session in a culturally safe and thoughtful way. The delivery of information was bridged by cancer care staff, and an Elder from the community who is also a cancer survivor.

Empowerment leads to early detection/treatment

The significance of inviting an Elder to speak is based on our knowledge that Elders preciously hold our stories, language, and legacy. I believe that when community cancer survivors are identified, a hope of cure becomes a possibility. It has been said by community members that at one time, speaking of cancer meant contracting it. By empowering Indigenous cancer survivors to speak up, they can support others entering into treatment, and inspire and support the Nation to become engaged in screening opportunities, thus leading to early detection and possible treatment.

As a residential school survivor and a registered nurse, Patricia has personally seen how health care for First Nations has evolved. She believes that if we continue on the current path, we are headed in the right direction. She states, “I am so proud and pleased to see First Nations people working in mainstream society, helping to bridge that gap of mutual respect and trust, by providing support to First Nations people wanting to access services that they don’t have at present in their communities.”

The window of change

Based on what she sees within the community, Patricia’s outlook for the future is optimistic. She has observed our people maintain a sense of humor, even after experiencing such separation and heartache. I agree with her, that we are in the window of change, a window through which we see open-minded and creative health care professionals adapting their practices to include Indigenous ways of being while working with our Indigenous clients.

One such group of individuals can be found once a month advocating for the equality and safety of Indigenous cancer clients during Indigenous Navigation Interprofessional Rounds. These providers are beginning to think creatively and are working to acknowledge the whole person. As the times have changed there is a need to change our ways of thinking. We need to recognize the importance of incorporating Elders, family, culture and tradition into our Indigenous clients' care plans.

One small, creative way that I have seen cancer care expand is virtual telephone appointments. These appointments allow for clients to remain in a comfortable, familiar environment and to be surrounded by the people who influence their decisions. In conjunction with other providers desiring change, Indigenous advocates are trying to do better through patient advocacy, provider education and promotion of Indigenous autonomy.

It would be wonderful to have more Indigenous leaders who can educate eager health care colleagues willing to learn our ways, traditions, and culture, so that our people feel safe and not judged when they want to incorporate traditional medicine into their care. For too long the mainstream health system has stigmatized and misunderstood the First Nations culture and way of life.

For the future, it is Patricia’s and my hope that we will continue to work together to repair the broken bridges that colonialism has caused and strive to incorporate the full spectrum of First Nations care: spiritual, physical, mental and emotional.

Banner image: Patricia Yellow Horn early in her nursing career