The events as they occurred

0930 hours, May 3, 2012 ... I was 57 years old

An unremarkable morning. Half an hour on the treadmill – training for the climbing season. Day started with two espressos – not unusual. Nose plugged, so added some pseudoephedrine nasal spray. Came off the machine tired with some vague chest discomfort. Within 30 minutes, the discomfort had become a massive vice encircling my chest, and my arm now felt ‘dead.’ When I called 911, the dispatcher asked me if I wanted him to stay on the line. I said “Maybe you’d better. I’m alone.”

That’s the very last thing I remember before being dragged out of a garbage can next to my bed by the paramedics – hypotensive, bradycardic and diplopleic due to bilateral retro-bulbar hemorrhages sustained in the fall. The initial ECG in the bedroom showed a large IMI (STEMI). An hour later, I was in a cath lab, being stented for a complete occlusion of the proximal RCA. The angios showed no atherosclerosis and there was never any antecedent angina in the days or weeks before the event. None whatsoever. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

1630 hours, November 15, 2016 ... I was now 62 years old.

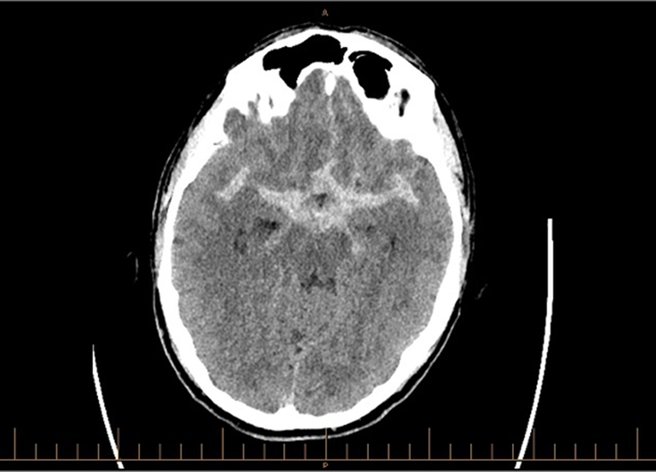

An unremarkable afternoon (in Florida). Reading a novel. There was an odd ‘crick’ in my neck followed by the sensation of a watermelon rapidly expanding inside my head and then the rapid loss of virtually all vision. Simultaneously, a massive ‘thunderclap’ headache, nausea and the sensation of imminent bowel evacuation. Vision returned slowly over an hour. By then, a CT scan showed a large subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH, combined Fisher and Hunt/Hess predicted mortality of 38%.). Only partial coiling was possible due to an arteriole from the aneurysmal neck feeding the mesial-orbital surface of my frontal lobe.

The days following in ICU are a blur. Part of it aphasic then speaking a word – salad. Confused, restrained and fully instrumented. On the full chemical potpourri needed to try to ride out the metabolic ‘storm’ and vasospasm in the week following. Aerovac’ed home on day 11. No antecedent ‘sentinel’ headache before the event. None whatsoever. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

What followed in the real world

After the STEMI, I was driving and at work in a month. Hiking and skiing followed after a year, climbing again at year three.

After the SAH, a return to administrative duties in one month and clinical practice (emergency medicine) two months later – working only in tandem for the first three months. Followed by the CPSA (still). Now practicing independently, but only half-time clinically (due to a post-SAH fatigue that will remain lifelong). Took me one month to be able to touch my toes. Back on skiis within six months, on a rope within a year.

What I learned

I’ve learned communication in the workplace is important. In the absence of that, something (anything) will fill the vacuum. Soon after the STEMI, I sent out an email with all the details. That way I knew the real story would get out. I didn’t have the luxury of early communication in the case of the SAH – and people are still coming up to me and asking how I am – following my devastating stroke, my massive car accident, my brain injury, etc.

I’ve learned to pay attention when all around you say you aren’t well. In the ICU (after the SAH) someone made the mistake of giving me my cellphone. I answered a call from the hospital head asking if I would take on the role of site lead in the ED. When I informed him I was in ICU, he added: “Oh, well, I mean – if you get out.” I said, “Sure.” On my return home, I found the contract already drawn up and the transition process essentially fait accompli. It’s taken me a year to extricate myself from that one word. And I had been told to stay off the phone.

Events like this can really mess you up for a long time. For emergency physicians, STEMI’s and SAH’s and their attendant morbidity stop abruptly ‘at the door.’ They simply vanish into someone else’s care and out of our lives. The other side of the door was new to me. Soon after the STEMI, I bumped into a doc in the hallway who had suffered an MI in his early 40s. I asked him, “How long does this mess with your head for?” His reply was two years, and so it has proven to be. Fearful of straining on the toilet, of carrying a bag of groceries, of doing a push-up, of getting angry, of having sex … fearful of anything. Glued at the hip to my nitro spray and BP monitor. Six months before daring to eat an egg. Now, I simply remember that it will take me longer to get on or off the mountain because I am B-blocked, to have my spray in the pack and to have my cellphone charged.

Life is inherently risky. My coronary angios showed no lesions, so I remain to this day largely an unknown quantity – albeit one with presumed ‘crème brulee’ patches on my arteries inherited from, well, everyone in my family tree. Likewise, I have an aneurysmal remnant pulsing with every heart beat that needs regular follow-up. But, truth be told, my biggest daily risk remains trying to make a left-hand turn on the way to work. It’s just a real head-wrap to trust in that truth and get back in the saddle.

No one gets through in life for free, and none of us is getting out of this alive. So we might just as well have fun with it along the way. In the ED, I have enough colleagues and staff now with stents in their chests to form a Walking Dead Club – momentarily lurching past each other whenever we cross paths in the hallway.

“Not if, but when,” my cardiologist says. And he’s on my side. No one knows when their first, or next, event will occur. So, sure, prepare for your future event (e.g.,) have your ‘Green sleeve’ in order, but live in the moment. Be intimate, present and engaged. That way, no one you love can say after the fact, “Meh, he was never really there.”

These events affected my family and our close friends greatly. Unexpected and imminent mortality right in their faces. I needed to be present for their reality as well, and they needed to feel daily that I was OK. And I really needed them. Robustness, resolve and resilience can only carry you so far – leaning on those closest to you provides the courage needed to return.

The real question: Why go back at all?

I had a good disability policy at the time of these events. I am near the end of a career in medicine. I could have been written up as totally disabled and walked away. But for me, emergency medicine has proven to be the greatest adventure ever. Where else would I want to be in the time remaining?

Oh … and where else would I rather be when my next event occurs than in my own emergency department?

Bonus.