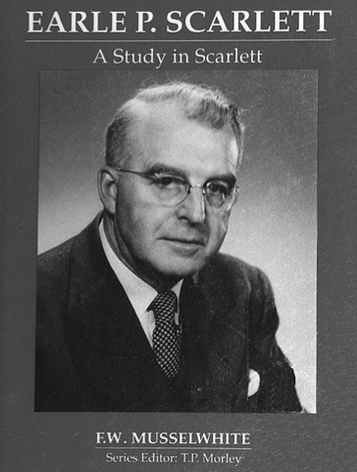

As I look back at 30 years of contributions to the Alberta Doctors’ Digest, there is one glaring omission – an introduction to Dr. Earle Scarlett (1896-1982). Few of us are left who knew him or have personal memories of his eloquence or his deep-seated concern over the decline in teaching the art of medicine. His own life was modelled after Dr. William Osler.

Scarlett’s ability to merge clinical medicine, cardiology and medical history with medical literature and the classics has no parallel in Canada. So voluminous was his body of work (over 450 publications) that it has never been compiled for study or thorough examination by the multidisciplinary team that would be required to establish his place in Canadian medicine.

Dr. Scarlett was a diamond in the wilderness, arriving in Calgary as its first cardiologist in 1930. Underchallenged, he found time to initiate and edit the Calgary Associate Clinic Historical Bulletin (CACHB), the first English medical-historical journal in Canada, which he edited for 22 years.

Scarlett was born in High Bluffs, Manitoba, in 1896, the son of Rev. Robert and Alma Scarlett. His early memories were of the paucity of toys but the abundance of books. At a young age, he would pull them off shelves for closer scrutiny.

His first literary effort was an article in his school magazine at age 12. Later, he would recommend to any listener: “always have a book in your lap and a pen in your hand.” Key points were to be found written in the back of almost every book in his library.

Scarlett completed his BA in 1916 and immediately joined the Army as a machine gunner. En route to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he dated and befriended a University of Toronto arts student. His wartime letters to Jean Odell revealed him to be an articulate fatalist, quite aware that the life expectancy of a foot soldier was three months and an airman six weeks. He survived the battle of Amien in 1918 but was badly wounded at Arras, 20 feet from Lt. Vanier, who was leading the charge by the Van Doos. Vanier lost his leg. Scarlett almost lost his life. Struck by shrapnel in the neck, he quickly became unconscious from blood loss. Rescued, he woke up in the Harvard Unit tent hospital and recalled rounds with his father and Boston physicians Richard Cabot and Harvey Cushing. During his eight-month rehabilitation in England, he was certain he was visited by Dr. William Osler.

Scarlett’s post-war vocational choice was to study medicine, a decision made after canvassing 12 professionals in his father’s congregation. He found only two were happy with their career choices. Both were physicians.

At the U of T, his extracurricular activities were those of a veteran. Expelled twice, he led the publication of the first undergraduate medical magazine in North America. As his marks dipped, his anatomy professor J. Playfair McMurrich called him in and gave him an ultimatum: “You don’t understand the difference between your vocation and your avocation. Now get back to your vocational studies.”

On seeing his name on the graduation list, Scarlett revisited McMurrich and asked him to explain his dictum. It began with: “Scarlett, what do you see in and above those cabinets?”

The response: “sculptures and drawings.”

“What do they have in common, Scarlett? They all relate to Michelangelo. Once or twice a year I am called to Europe to authenticate a Michelangelo artifact. That is my avocation. My vocation is medicine – it is a means to an end. The end is my avocation. Now get on with your life, but don’t forget your avocation.”

Dr. Scarlett frequently retold this story to encourage students to venture beyond their professional training, to complement their lives with avocations. “Become medical truants,” he would say, “like Keates, Shelly or Conan Doyle.”

After he recounted the story to me in 1977, he asked me what avocational interests I had. I replied, “The Rocky Mountains – climbing and scrambling in them – but because of my 1971 knee injury, I expect they will be self-limiting.” He then pulled out a book entitled Climbing Days by Dorothy Pilley. The author was the wife of one of his close friends, the Oxford professor of English I.A. Richards. The couple had climbed together in the Alps and had spent two summers at Lake Louise. Her description of their experiences is an exceptional piece of mountaineering literature. In the front was a personal letter to Dr. Scarlett. It was characteristic of him that any story a visitor would share, he would finish not only with a richer one, but usually one in the first person.

After graduation from medical school, Scarlett found himself with 25 cents in his pocket and no debts, so he promptly proposed to Jean. Six years of post-graduate training followed, leading to a fellowship in internal medicine with a sub-specialty training in cardiology and a return to the city of his honeymoon, Calgary, or the “Baghdad on the Bow” as he termed it. There he joined a group of specialists that had already formed the Associate Clinic.

Clinic leader Dr. D.S. Macnab’s weekly two-hour continuing medical education luncheons were soon augmented to include monthly historical nights. On Dr. G. D. Stanley’s prompting, in 1936 Dr. Scarlett agreed to co-edit the presentations at the clinics’ historical nights into the Calgary Associate Clinics Historical Bulletin (CACHB).

Dr. Scarlett wrote a regular column in it entitled Medical miscellany – The commonplace book of the medical reader. Under this rubric, he recorded his latest readings on a wide variety of medical subjects. To expedite the writing of his columns, he began “The ram’s horn”: his own commonplace book of notes and quotes for future use.

Dr. Stanley covered local medical figures in his column. As it matured, the CACHB expanded to deal with the “peaks” in medical history – Hippocrates; the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman eras; and medieval medicine. Scarlett co-opted clinic members, friends and acquaintances to write the articles. Each Canadian medical school was covered. The last issues highlighted early North West Mounted Police doctors.

Dr. Scarlett’s lifelong interest in education led to appointments to the U of A Senate and Board and as its Chancellor from 1952-1958, before his retirement from practice in 1958. Then the Scarletts headed off to Greece and the Island of Cos, where Hippocrates had taught, for 15 months of rejuvenation. On his return, he accepted Premier Manning’s request to join the Foothills Hospital Board in 1960.

In 1964, the Royal Commission on Health Services projected a major deficit in the number of physicians needed in Canada and requested four new medical schools be built. An AMA committee visited Dr. Scarlett to see if he would support one in Calgary. He agreed but advised them not to disrupt the mature medical program at the U of A.

Before the Foothills Hospital opened, Dr. Scarlett was asked to provide a vision statement. His answer was engraved in the marble slab at the entrance, acknowledging its new role.

In a second inscription for the foyer, unveiled by Premier Manning at its opening on June 10, 1966, he described life in the hospital.

A decade later he provided his own expectation of the staff working in the new Special Services Building that provided cancer, auxiliary, radiological and other services.

His ability to inspire others was never lost. During a “Wednesday with Earle” evening in the late 1970s, he inscribed a copy of his anthology, “In Sickness and in Health,” for my son Bruce, who was 10 at the time.

Fourteen years later, Bruce graduated in medicine from the U of C.

Scarlett’s reputation was such that the City of Calgary named the EP Scarlett High School after him in 1967. He spent many hours in its library, listening and asking questions, and sharing his philosophy on life. Medicine, he said, was more than a science – it was also an art, as he encapsulated in the 10th-anniversary issue of the CACHB.

Banner image credit: Profiles and Perspectives from Alberta’s Medical History