Renamed the Cumming School of Medicine in 2014, the school celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2020 – in COVID style, with little fanfare, semi-closed facilities, and as much remote learning as possible.

This year, the CSM reached another milestone. It is half the age of the U of A school, which celebrates the 100th anniversary of the first full-degree class entry in 2021. Together the two Alberta medical schools now graduate more than 300 physicians per year. That was the self-sufficient goal set by the Hall Commission back in 1964 when it recommended four new schools in Canada, setting off the largest-ever expansion of Canadian medical schools. The majority of the more than 4,000 CSM alumni now practice in southern Alberta, with 80% of those in Calgary.

Back in 1967, Calgary was the largest and fastest growing city in Canada without a medical school and, until the previous year, no autonomous university. The new faculty began its life at the tail end of the baby boom that had dramatically affected universities. The U of C struggled in the competition for capital and operating funds.

Starting a new school was an opportunity and a challenge. Fortunately someone was prepared – Dr. William Cochrane at Dalhousie. He had visited multiple centers in the U.S.A. and concluded that medicine could be taught on a system-by-system basis, as Case Western Reserve in Cleveland had been, and in a continuously taught program that reduced the length from four years to three. With no basic science departments to object, it was a perfect opportunity to be innovative. Dr. Cochrane’s arrival brought a youthfulness and enthusiasm that would encourage younger faculty to choose to teach in Calgary.

To develop the new curriculum, Dr. Cochrane brought in anatomist Dr. David Dickson to painstakingly define the core knowledge to be taught. In practice, the curriculum became what a family practitioner needed to know or what a student needed to know to pass the LMCC national exam.

The shortage of faculty at the school led to a huge reliance on local physicians to design the curriculum and teach it, using the new concept of clinical teaching units, which limited teaching on patients to the time they were educationally interesting.

The site development proceeded at a rapid Calgary can-do pace. The Foothills Hospital was accredited in 1967, received interns in 1968 and residents in 1969. After three more site accreditation approvals in 1970, the first class of medical students arrived in September. It was only possible after a three-floor addition to the hospital’s west wing.

The cost for the school was settled over a case of beer on the Bow River in 1969, increasing it from $15M to $25M. With efficient project management, the construction time was halved to 30 months. The final cost of $20M left funds behind to renovate the empty research space. The school included a clinic for family physicians and specialists to see patients and teach on them.

A potentially lethal blow came with the federal oil royalty question not settled and a new (Lougheed) government determined to balance its budget. This curtailed university funding so severely in 1972-73 that, in desperation, unspent construction funds were transferred to the school’s operating budget to cover the deficit and avoid having to close the school.

The first class began with 32 students even though the curriculum hadn’t been finalized. Everyone rose to the challenge and the first graduation exercise was held as part of the official opening of the medical school in May/June 1973. The students did well on their LMCCs to everyone’s relief. With that success, the word was out that the U of C program was viable and had the added advantage of selecting students from a wide range of backgrounds.

With no research space, the faculty had been “rusting.” By 1978 all the empty space was allocated and in use, as the Lougheed government began entertaining “brain industry” applications leading to the establishment of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) in 1980. Whole research teams came to Alberta. The U of C program had an advantage as its teams had developed around each body system and were multidisciplinary from the start. Departments without strong research activities were not so advantaged.

A new Heritage Medical Research Building was completed by 1987. In time, that five-storey addition was insufficient too.

Oil prices progressively decreased in the 1980s, and a rapid correction was instituted in the 1990s, leading to a 25% reduction in hospital services and a 10% reduction in faculty enrolment. Individual hospital boards were merged into regions, and the Holy Cross Hospital and Calgary General Hospital were closed. The Alberta Children's Hospital was almost closed too, as governments sought to implement the Barer-Stoddard recommendation that decreasing physician graduates saved $500,000 per doctor. In the end, the school was saved by public protests.

Recovery came as the price of oil increased. The rags-to-riches story funded the new Children’s Hospital, opened in 2006 – the first new one in Canada in 30 years.

On its 25th anniversary, the faculty revised the original curriculum and reorganized it by following the 120 most common clinical presentations. Although not fully problem-based, the curriculum drew international attention as a way for mature faculties to more clinically orient their 2+2 (basic plus clinical) curricula.

In a successful proposal for a veterinary medicine school, the faculty used the same clinical curriculum approach – teaching on a systems basis while using local veterinary facilities for the clinical experience.

Starting in 1980, interested faculty members took locums or sabbaticals to help develop and teach at new medical schools, starting in Kathmandu in Nepal, then the Philippines and Laos. Consulting advice was provided to many more third-world faculties. Affiliation agreements and partnerships were signed with scores of other schools, which led to international students coming to study in the faculty and undergraduate students choosing electives at the affiliated centers. The world-wide Global International Health Program has become one of the proud achievements of the faculty.

By 2006, the continued pressure for more space led to the construction of two more facilities (the Health Research Innovation Centre and the Teaching, Research and Wellness Building). The Foothills Hospital underwent another expansion of its clinical facilities into the McCaig Tower in 2012, making it the largest medical center in Alberta.

A sad but not fatal event occurred with the demise of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research in 2005. It corresponded with the approval of seven research institutes (2004 to 2009) that focused the faculty’s research efforts. The community responded significantly to the faculty’s requests, raising $51M in the Partners in Health campaign in the 1990s and $312M in the Reach! Campaign that finished in 2010.

The educational programs remain current and under continuous improvement. So far, the faculty has maintained a 100% record after undergraduate, postgraduate, family practice and continuing medical education accreditation visits. Although a prodigious effort has been required to meet rising standards, more solutions like the Lindsay virtual self-learning anatomy program designed by the engineering faculty have been groundbreaking.

For southern Albertans, the breadth and quality of medical care at the Cumming School of Medicine has become leading edge, and in some cases, internationally recognized.

A great foundation has been laid, although it can be expected that fluctuating oil prices will continue to lead to less government funding and higher tuitions, while external scrutiny will remain a costly driver.

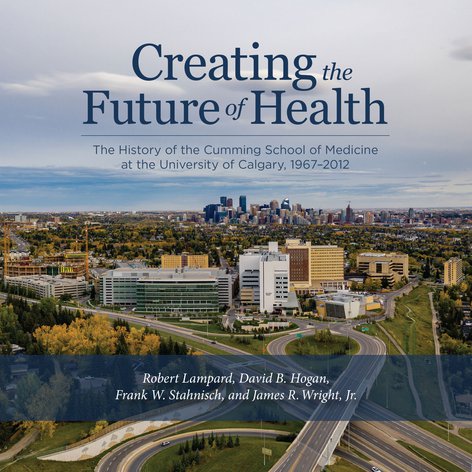

You can read more about the success story in Creating the Future of Health: The History of the Cumming School of Medicine, released by the U of C Press in March 2021.

Banner image credit: University of Calgary