After 63 years of fun, fellowship and potential referrals, including 54 years of participation, I attended what may be my last Western Medical Curling bonspiel from March 11-14. It was a memorable event, not for what happened on the ice, but off it. Centered at the Granite Club in Edmonton, it was unknown to anyone attending that a super-spreader of the COVID-19 virus was in attendance. That said, it could have been worse, had the first case of COVID-19 not self-isolated after his first game.

What happened?

In early March, Canadians were beginning to recognize how rapidly the COVID-19 virus was spreading, particularly by international travellers and by silent or asymptomatic spreaders. Hospitalizations and deaths were already known to be age related – skewed to those particularly over 80. Eventually, that connection would impact long-term care facilities disproportionately. It was a new virus, though similar to its predecessors: SARS, MERS, Ebola, H1N1, and the annual flu. But there were important differences in spread, morbidity and mortality. And there was no vaccine or known effective treatment.

The virus was just reaching Canada. There were 19 cases in Alberta and one in Saskatchewan, all thought to be from international travel. The Oilers were still playing the Jets on March 13. On March 19, the federal government banned international travel and closed the US border on March 20. The Alberta government closed classes and reduced the maximum group gathering size from 250 to 50 on March 19.

The forward-thinking bonspiel organizers, who had been planning for over a year, anticipated the impact of the virus. All participants were asked to particularly avoid handshakes, replacing them with the Cumming School of Medicine fist bump, or bowing or using a Vulcan “live long and prosper” greeting. Curling rock handles were hand wiped before every game and sanitizers were made available for the 19 teams, including 73 curlers (53 doctors) who came to compete. Two CME presentations during the buffet lunches were integrated into the program. Socially there was a pre-bonspiel evening with a Calcutta to predict the winners, followed by bowling the second night and then the Oilers game. After five games of curling over the next three days, the finals, which 60 attended, were held on March 14, followed by a banquet with presentations to the winners.

One member of a Saskatchewan team had just returned from a vacation in Las Vegas. Unknowingly, he became the second COVID-19 case from Saskatchewan. Identified as patient zero, he had already curled a game three days before the bonspiel, from which two cases would later arise. Initially asymptomatic, he developed mild respiratory symptoms the first morning of curling. Showing abundant caution, he played only one game and attended the CME luncheon before he self-isolated and returned to Saskatchewan. Two days after the bonspiel, his test results came back positive on the evening of March 17.

On March 18, the bonspiel organizer was informed. The curlers who attended were notified of their potential COVID-19 contact and requested to isolate themselves for two weeks. The next day, Dr. Allan Woo, the president of the Saskatchewan Medical Association, tested positive and released an alerting letter to the group. On March 19, the Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Deena Hinshaw, was informed. Unfortunately, most medical curlers had already returned to their practices, which required contact tracing by medical students and others.

Calgary School of Medicine Associate Dean, Dr. Kelly Burak, a trained epidemiologist, began accumulating case-by-case information and released daily updates to all the teams in the four provinces represented at the bonspiel. He, too, would become ill with the virus even though he initially tested negative. Everyone was surprised and then alarmed at the rapid increase in cases to 20 and then to 40 and more.

Our team was no exception. Two of four became positive, as did two wives. My own symptoms began 11 days after the bonspiel. Despite constant interaction with my identical twin brother throughout the bonspiel, he never showed any symptoms. Given my venerable age, in a bracket where over half of the deaths have occurred, my two physician sons became quite alarmed at the risk of a serious outcome. Tested on March 24, my first symptoms started later that day with the sniffles, nasal congestion and a drippy nose. They progressed over the next 48 hours to a dry cough, low-grade temperature, some neck pain, increasing tiredness and a loss of sense of smell. But the worst symptom was the fatigue. After 24 hours of sleep, a slow recovery began, although the coughing continued. Quarantined at home, there were no visitors. Food was brought to the house by friends and left in the driveway to be picked up. Not surprisingly, my wife began to show symptoms with anosmia, diarrhea and a mild cough – a presumed positive case. That extended the isolation requirement. Fortunately, there were no permanent sequelae.

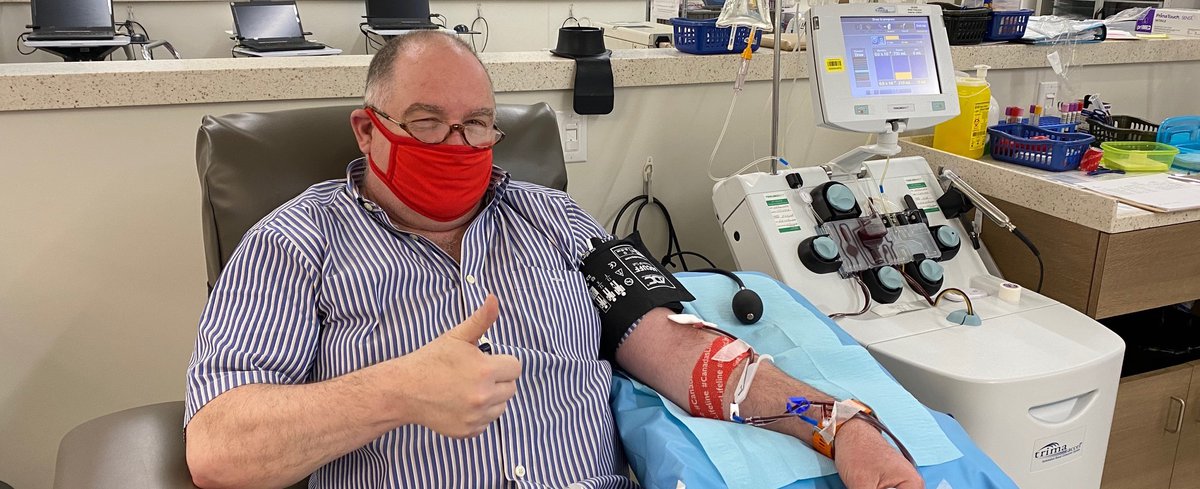

Within the curling group, one physician was sufficiently ill to visit the ER but was not admitted. No one required hospitalization. Forty of 73 curlers tested positive. Another 16 developed symptoms but had negative swabs or were not tested, for an attack rate of 77%. Six had false negative swabs, which were positive on re-testing. Two unusual signs were the frequent loss of smell and diarrhea (in over 70% of cases). Many with sufficiently high titres donated convalescent serum to the Red Cross. As one sage said, “Now we are the most immune curling league in the country.”

It could have been worse. Had patient zero not self-isolated almost immediately and been quickly tested, the local and secondary spread would have been more extensive. As far as is known, no spread to other health care workers and patients occurred, just family. Dr. Burak worked with provincial health officers to set rules governing testing, isolation and return to work for the whole province. Information was accumulated and shared through five webinars, and an article abstract was submitted to the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Like other cases across the country, the coordinated Canadian response to the crisis has been encouraging. The positive case rates have been 20% of those in the USA, and the death rate 50% of the American rate, despite the 50% higher health care spending level in the USA.

The initial feeling of shame, as portrayed in the newspapers, does not reflect the leadership shown in addressing a potentially widespread problem. Congratulations to everyone involved for controlling the spread which could have been much worse.

Banner image credit: Monica Volpin, Pixabay.com