I’ve had a fear of heights since childhood – ever since being taken up the Walter Scott Monument, a sandstone spire, blackened by years of soot and smoke, some 200 feet high, completed in 1844 on Princes Street, Edinburgh.

It was the height of the tourist season and, age 5, I climbed the worn, narrow stone spiral staircase holding my mother’s hand as a stream of visitors climbed down noisily, pushing us outward against the stone wall with my mother stumbling and tightening her grip as I was dragged onto the small top observation deck to view the panorama – and the 200-foot drop. Visitors pushed and shoved. A fresh case of acrophobia was born.

Since then, I cannot comfortably climb stairs in tall buildings, although I can grit my teeth and use the elevator to reach the 58th floor of the Bow Tower in Calgary where Prof. Gwyn Bebb likes to hold his precision oncology meetings – as long as I don’t go too near the ceiling-to-floor windows. I made the second level of the Eiffel Tower in Paris – the level you reach by walking up see-through iron stairs to reach the elevator that whisks you to the top. But I gave up there.

Notre Dame freaks me out. I hug the inner wall trying to suppress the waves of nausea as I watch some kid sitting nonchalantly on the outer stone walls at the top. Even an old photo from the 1930s of building laborers having their packed lunch sitting on a girder at the top of a New York skyscraper can elicit a panic spasm.

You’ve got the point – I have significant acrophobia.

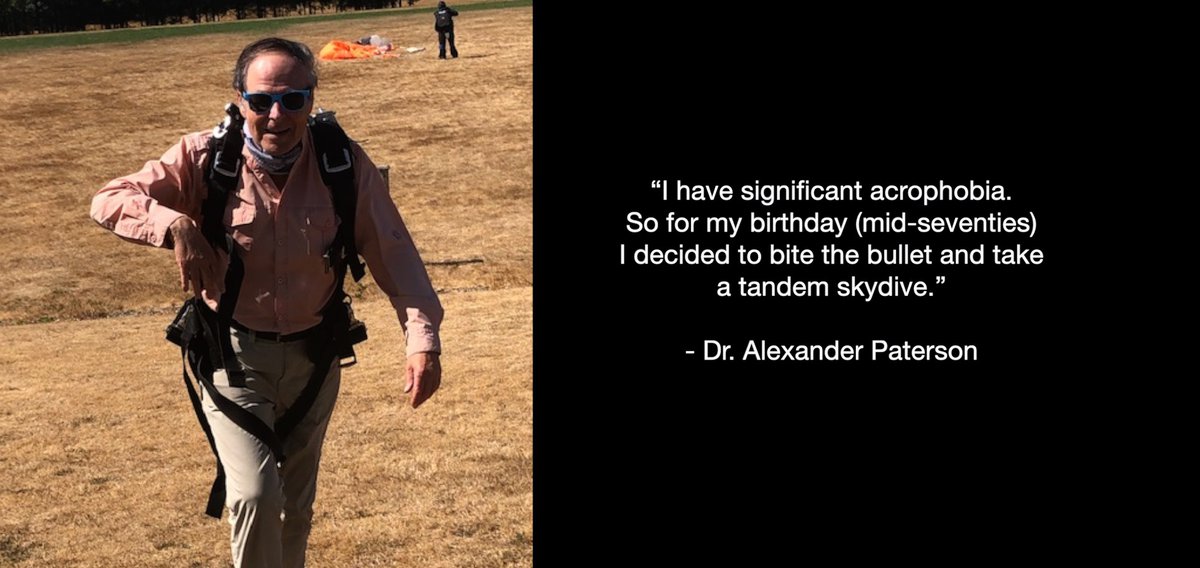

So for my birthday (mid-seventies) I decided to bite the bullet and take a tandem skydive with Vancouver Island Skydive at Arbutus Meadows and Equestrian Centre, at Nanoose Bay, near Nanaimo. I phoned the amiable, cheerful and knowledgeable Alison, joint owner of the small business. The consent and waiver? I admitted to stable hypertension and being on several anti-hypertensive drugs, signed the internet document with a flourish – agreeing to anything and everything and spent the next two days with a low-grade anxiety in the pit of my stomach. I asked some friends to buddy up, but for some reason they backed off.

I’ve no fear of flying in a well-built aircraft – though a good bout of sudden moderate turbulence (the kind pilots call “light”) has me grabbing the sides of the seat and wondering what I’m doing in an aluminum tube at 36,000 feet.

The kids were a little worried.

“They had a bad accident last July,” said my son. But I knew about that.

“It was a really experienced diver doing a highly complex ‘swoop’ landing,” I said. And to calm them down I admitted my dive would be a tandem skydive – the kind that a 103-year-old in a wheelchair can handle, being hitched to an experienced skydiver who will break the landing fall.

Gord Gauvin, co-owner of Vancouver Island Skydive, looked me up and down. I was dressed lightly with long-sleeved shirt, long pants, Puma-laced sand shoes and my Keith Richards headband holding the stupid hair comb-over in place.

“You look active. You’ll be OK. Let’s go to the hangar and get you fitted up. How d’you feel?”

“Nervous,” I said.

“That’s normal,” said Gord cheerfully.

In the massive hangar, I stepped into the body gear with buckles hanging down everywhere, and Gord tightened the straps around the gluteals and shoulders. I shuffled over to a table and lay face down while Gord tried to get me to extend neck, back and legs to look like a flying banana – the position to adopt when free-falling from the aircraft. It was a struggle.

“It’ll have to do,” he said. There were other instructions which went in one ear but no further.

We were transported by van to Qualicum Beach Airport where a Cessna 182 – the Clydesdale horse of the small airplane world – was being gassed up, and we clambered aboard. One other skydude was already there.

“What’s your dive count?” I asked him. It’s the way we divers chat to each other.

“This would be my …” and he paused, “… one hundred and thirty-second.”

The little Cessna was modified for skydiving and had seats only for the pilots. The diving jump-door and step was on the starboard side. We three divers sat on the floor facing the back of the Cessna as we rumbled down the runway and took off. The view was magnificent – Texada and Lasqueti Islands in the Georgia Straits and mountains to the north and west with Nanaimo in the distant south.

We hit turbulence at 2,000 feet and the aircraft pitched and rocked. It’s interesting how having something more serious to think about like jumping out of an aircraft at 10,000 feet via an open thin metal door puts worries about turbulence into the background.

At 8,000 feet, I was hooked up to Gord, good and tight in a doggy-style copulatory position, with thumbs in the chest straps like a boss expostulating to the staff with his thumbs in his lapels. “Use my belly as a cushion,” he said. “When the jump-door opens, Tom goes first then we push up to the open door and you put your feet and legs dangling out of the aircraft.”

“Ah,” says I. I was chewing gum and realized that jumping out into high-speed air with gum in the mouth was not the smartest move and might end with a bronchoscopy. The gum went into my pocket.

Ten thousand, shouted Eric, the pilot. The jump-door opened, and there was a rush of air and engine noise. Tom, the experienced diver, put his legs over the aircraft door’s edge, stood on the platform step, let go of a side-handle, stepped off – and by God he was gone!

Gord grabbed me by the thorax and pulled me towards the open door like a lifeguard dragging a drowning swimmer to shore. My brain registered two conflicting ideas – the first was to get as far away as possible from that open door to safety at the rear of the Cessna aircraft, but the second was knowing I had no choice but to push my way to the roaring rush of the open aircraft door.

Gord already had one leg out, and he shouted to get my legs out over the edge and stand on the platform! I felt a tug on my head and remembered that I had to look up – sort of what I would do if I were standing on the trapdoor of a gallows without a blindfold.

Suddenly there was a screaming of air. We were free-falling, and there was an uncomfortable pressure in my ears – not so much a pain, more like both eardrums were letting in air. I don’t remember seeing the little pilot parachute deployed nor much more about that free-fall other than that 170 km/hour was likely the speed at which we were falling. A tap on my shoulder and I remembered I should open my arms out and try to take up the flying banana shape. It may have been then that my Keith Richards headband departed and may have floated down onto a cottage rooftop or in a field to be discovered by a puzzled archaeologist a millennium from now.

Then a sudden pressure on the shoulders as the parachute opened. I blinked, and we were floating in blue skies with a few puffy clouds over the sea. Gord held out two stirrup handles which allowed us to steer the chute. He encouraged me to take hold of them. Grabbing hold of the left one we veered sharply to the left in a stunning glide which made me slightly nauseated.

“It’s better to use both hands,” shouted Gord, and he demonstrated how to pull on one side and push up on the other leading to a smooth, gracious curve, which caused only a minimum of mild nausea. We did two or three of those for the benefit of folks on the ground taking photos. The soft sound of air rushing over the chute was peaceful and relaxing. My instructor pointed out Rathtrevor Beach and then at a tiny quadrangle of grass 5,000 feet below – the landing spot.

As an aficionado of second world-war movies where the soldiers or spies landed however they could – up a tree, skewered by a branch or rolled over and over by a dragging parachute – I was doubtful of success to hit this postage stamp of grass.

We soared and circled, and the postage stamp became laptop-sized, then mat-sized, and the only obstacle was then the tall hangar between us and the landing spot. I was now pretty confident that we’d glide over the roof of the hangar and we did, descending at a fair lick.

Gord yelled to lift up my legs, and he flared the chute and executed a perfect landing, holding me like a really heavy dog. Maybe I had some brain ischemia, but I stood there enjoying the solidity of the earth on the legs until Gord unhooked me, we high-fived, and I said something like “Wow, sensational,” and walked over to wife and friends waiting and taking photos.

Post-flight, hearing was a bit different, possibly wax which had sunk further down the canal, and my brain seemed a little shell-shocked because it kept instructing my mouth to keep blabbing about how great it all was. Or maybe it was the adrenaline rush. The tension anxiety in my belly had gone.

A recent French publication in the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport (May 2021) reported a prospective cohort study on the epidemiology of skydiving between 2010 and 2019, standardized between skydiver’s sex, level of experience (tandem, student, experienced), by deaths and injuries. Results were expressed as rates per 100,000 jumps and per 1,000 skydivers. In 6.2 million jumps by 519,000 skydivers, there were 35 deaths and 3,015 injuries giving rates of 0.57 deaths and 49 injuries per 100,000 jumps. There were no deaths in the tandem jump group. There were five times as many deaths in males as females, and student skydivers had six times as many injuries as experienced divers. Tandem skydivers have an even lower risk of injuries: 83% of injuries occurred during landing, most in the lower limbs. Of course, it’s the experienced divers taking risks where the mortality occurs.

So, if you want a different, safe and memorable experience, I can recommend a tandem skydive.

Did this cure my acrophobia? No, not completely, but it seems to have helped a bit. I can look at a photo of men working on tall buildings with no safety gear without feeling a wave of nausea. This means I may have to take a skydiving course this winter and do a few solo jumps in spring 2022.

Editor’s note: The views, perspectives and opinions in this article are solely the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of the AMA.

Banner image credit: Sally Hatchwell