“First times” are a celebrated rite of passage. Milestones in our life-journey, moments that shape who we become. Watching my colleagues across Alberta in this time of COVID-19 has me thinking about a specific first time, memorable because it was the first time I witnessed racism as an “insider” within the health system. I was a medical student in my third year of training, rotating in emergency. I still remember how excited I was to be set loose to apply my limited learnings to real life patients under the watchful eyes of residents and staff.

It was a cold winter night when the two patients arrived one after another, dutifully assigned to adjacent emergency beds. They both had the look of men whose lives had not been overly kind, with eyes that were lonely and faces that had seen too much disappointment. Their presenting symptoms were similar: disorientation and slurred speech. As I eagerly initiated the intake of both patients, the differences in how we approached each of them was slowly revealed.

Patient 1 received an intravenous, a medical history was attempted (but failed) and bloodwork was drawn. Imaging was ordered. As I walked to patient 2, a nurse called me over to the desk. “Don’t bother with him,” she said. “He comes in drunk every other week.” I proceeded anyway with another unsuccessful medical history. “He’ll just sleep it off,” said another nurse reassuringly.

Over the next few hours, patient 1’s bloodwork and other investigations returned. We methodically crossed off each differential diagnosis. Stroke unlikely based on imaging. Chest X-ray is clear. Glucose is normal. Doesn’t look like the troponins are elevated. Supported by bloodwork, we settled on a diagnosis of low-level acute alcohol intoxication. His intravenous ran throughout the night as we waited for his body to do the rest.

Patient 2 laid in his emergency bed with warm blankets placed over him. The nurses weren’t unkind, occasionally dropping by with a new glass of water or a nighttime snack box which laid unopened beside patient 2’s bed. They were convinced that his problem was acute intoxication, even though no objective evidence had been gathered. No differential diagnosis. No bloodwork. No imaging. We didn’t start an intravenous. I imagine you may have already concluded that patient 1 was white, while patient 2 was Indigenous.

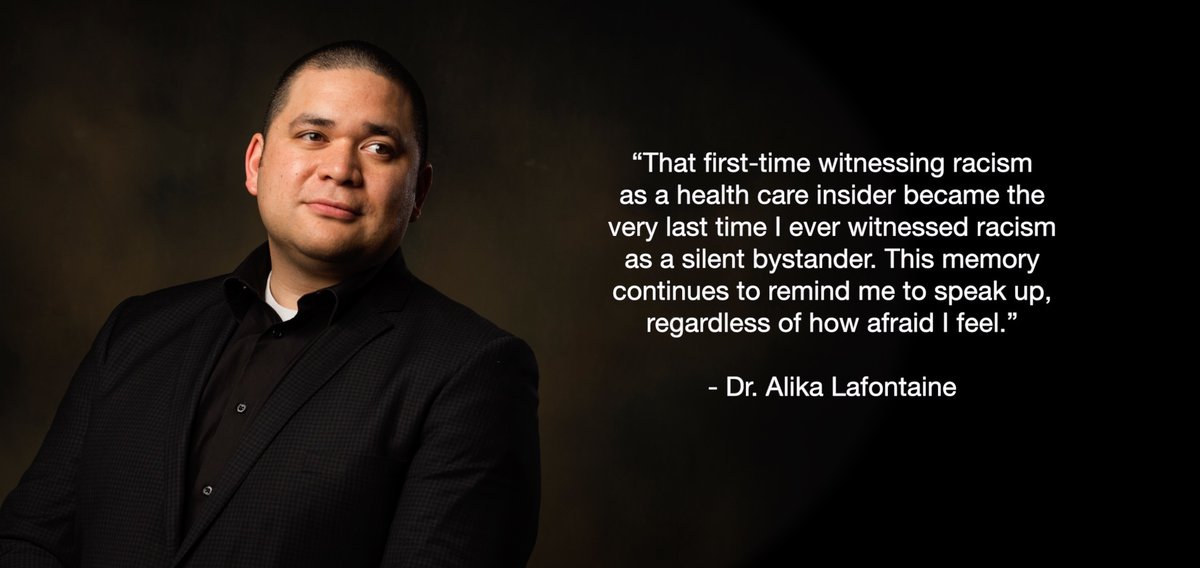

There are a lot of abnormal norms within medicine. Ways that we treat patients and each other that we know inside aren’t 100% right. This doesn’t mean that the people who act this way are totally bad people, in fact they usually are good people. This reality is what makes us pause when we feel the need to speak up. It was these feelings that held me back as a medical student all those years ago. I didn’t want to offend. There was obvious discrimination, but not complete rejection. I knew the differential treatment wasn’t right or proper medical care, but not so wrong and improper that it overcame my fear of speaking up. That first time witnessing racism as a health care insider became the very last time I ever witnessed racism as a silent bystander. This memory continues to remind me to speak up, regardless of how afraid I feel.

Throughout this pandemic there have been countless abnormal norms that physicians have spoken up about. The need for personal protective equipment when demand outstripped supply. Speaking up about the differential impact of the initial lockdown – which included much of the medical system – and the adverse, non-homogenous impacts on vulnerable patients. The magnification of pre-existing gaps in care, especially those within long-term care and assisted living.

The aggregated impacts of years of fiscal austerity on the health care system as our infrastructure and human resources become overwhelmed. The requirement for a second lockdown, as voluntary measures fell short. The moral injury we face increasingly as we see the unjust distribution of sickness on the vulnerable and disempowered. The reckoning that physicians face regarding burnout we all sense is over the horizon on the other end of this pandemic.

Indigenous scholars have long said that truth comes before reconciliation. The truth of what needs to be overcome to resolve this pandemic is becoming increasingly clear and the courage is being found to say those truths out loud. You are speaking up despite the fear of retaliation from armchair epidemiologists and more official antagonists. You are thoughtful, respectful, measured; even forceful when necessary.

I encourage you to find that same voice for all the areas in health care that require change. We all know that Indigenous patients suffer widening health disparities. We also know now that those disparities aren’t just from gaps in care (which are many), but also from racism (which is a social determinant of health). Take that same courage and continue to speak up.

A silver lining of this pandemic has been physicians finding their voice. I hope we’ve also realized that in the face of abnormal norms, remaining silent is no longer an option.

Banner photo credit: Dr. Cara Bablitz