The Economist of February 3, ran a gee whiz leader announcing that Big Tech firms were poised to disrupt and transform health care and that this time, after several previous unsuccessful raids and forays, they meant it.

The fundamental problem with today’s health system – according to The Economist – is that patients lack knowledge and control. Wow – like – “Hello” – this is – like – revolutionary! Three Industry Titans – Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan Chase – are teaming up and aim to provide better, cheaper health care to their employees by giving them knowledge and control through custody of their health record.

Empowering patients with information is fine, but what they do with the information is important too. It makes me think of the words of Sir William Osler, the great Canadian and British physician: "A physician who treats himself has a fool for a patient."

Self treatment aside, a fair prediction is that it may indeed be better in some ways to give patients knowledge and control through custody of their health record. But, oh no, it will not be cheaper, not by a long tab.

How are they going to do it? By empowering patients, improving diagnostics and therapeutics, and slashing costs! Well, we already have empowered patients; killer apps called “digiceuticals” are being designed – some may be useful (who knows?). But as for slashing costs, tell that to the Irish Marines.

Forgive some skepticism here as we in the developed world hurtle headlong and pell-mell into an era of machine artificial intelligence and advanced information technology, with precision medicine, 3D printing, driverless cars and the Internet of things, leaving the rest of the planet’s medicos gasping and clutching their plastic stethoscopes, rubber tendon hammers and relying on history and physical examination.

And let’s spare a thought for those who do not relish being permanently riveted to their mobile gadgetry and spending more and more of their waking hours focusing on a patch of light on a hand-held oblong device. And spare another thought for the increasing numbers of folk who can only manage a text or an email or two but who fear booking things online, detest online shopping and suffer nostalgic aches for the lost days of knowledgeable, breezy travel agents, face-to-face discussions with colleagues and hand-written letters sent in the afternoon and arriving in your post box the next day.

We dance faster and faster to the jigs of the hucksters and hawkers of Silicon Valley with their climate-changing energy consumption, their sly, subversive goal of infiltrating and monitoring your whole life so that every byte of data from banking to sex passes through their little gadget, and their promotion of addiction to this gadget which some believe has led to an epidemic of mind-numbed, depressed, head-drooping teenagers unable to see the world around them. It appears that the busybodies and masters of the universe are no longer content with disrupting the taxi and hotel industry, but they now want to interpose themselves into the healing art, the health care industry and the physician-patient relationship.

Yes! They are poised to inflict more cervical spondylitis by disrupting health care and imposing game changing paradigm shifts onto the lives of ordinary people who will require spending more of their solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short lives staring at the pretty icons of the single most useful yet isolating gadget ever invented.

So this diatribe is not to challenge our excellent Dr. Gadget (Dr. Wesley Jackson) columnist at Alberta Doctors' Digest, who writes lucidly and informatively on the latest electronic applications and on artificial intelligence, but to say (as Dr. Jackson does) that many apps are over-hyped and to emphasize yet again the critical importance of empathetic communication and the healing comfort of a taking a good history and performing an expert physical examination.

You just need to observe my good friend and former neighbor, Dr. Steven Aung, practicing in his Edmonton clinic where patients are willing to wait many months to have their chronic pain discussed and examined in detail. The doctor-patient relationship will never change, whatever disruption Silicon Valley wants to throw, although the supporting equipment certainly will change.

First though, I should declare a conflict of interest as holder of my patented PaperChart© which will outlast the electronic medical record’s fragile, jumpy electronic blips of transient energy and which will be readable by grateful researchers in 2,000 years and more. As a weary viewer of the over-hyped wonders of digital life, I aim to briefly peruse the claims from IT companies as to how they plan to disrupt health care and save everyone money. I don’t mean those smart medical devices and equipment which have so much improved diagnostic radiology, surgical techniques and medical treatment abilities. I mean skepticism of the digitization of everything – except, of course, our current digitization of Alberta Doctors’ Digest – which (it goes without saying) is a neat advance.

Tech skepticism in action

On a rainy Wednesday evening in March, a plane load of weary travelers from Hong Kong, dragging their worldly (sorry, planetary) goods into the arrival hall at Vancouver International Airport, were greeted with a proud announcement that YVR had implemented a new customs and immigration system (suitable for this modern age) of individual kiosks for passport and immigration control. This would do away almost entirely with human beings. However, the scene in front of us was more like something you’d see at the check-in counters of Uzbekistan Airways (a third world rammie*). Six lines of machines standing like colorful parking meters greeted us. These were the immigration kiosks.”

As we stood in front of this artificially intelligent machine, it commanded us firmly but politely to take out our passports and to place them on a screen. Most of our fellow stupid passengers were placing them incorrectly – either inside out, upside down, wrong page or the wrong way round. The machine asked multiple questions, the answers to which we clicked yea or nay. Then nervous human “helpers” rushed around pulling people back from the machine or pushing them towards the machine to have their photos taken because they were standing either too close to the camera, which hovered over them like the head of a cobra about to strike, or they were not close enough. One elderly woman burst into tears when the machine shouted at her to stand further back, then to come forward, then further back again, then again forward, and then, giving up, fell silent.

Suddenly a whistle blew and the melee was called to a stop. “None of the kiosks are working,” announced an attendant. “Everyone’s having trouble!” And the airport helpers then rushed around handing out those old paper landing cards to be filled in the usual way in French or English with those helpful little kiddie squares that encourage you to write each letter into an individual box. We then lined up to be interviewed by weary, frazzled human customs officials who asked us where we had been and what we had brought into the country. This multi-million dollar kiosk contract will not do much for airport security or human employment rates, but will be great for ID kiosk manufacturers such as Border Express. I harbor, you understand, a mild skepticism regarding the wonders of machine-based security.

The best airport security I’ve experienced was travelling on Indian Airways, flying from Delhi to Bangalore. A huge man in khaki and full turban shoved me against the wall of the security area with his shoulder and gave me a total body rub down and massage falling just short of a penetrating rectal exam. He then took my boarding card and stamped it “FRISKED.” I boarded that flight knowing with absolute certainty there were no armed miscreants aboard that flight. Do you have the same level of comfort and security with the full body scanners and X-rays of your baggage surveyed by sleepy, bored security people staring at screens? Perhaps you do, but you shouldn’t. The miss-rate on random testing is around 60%. The miss rate for my security man at the Delhi Airport would be 0.0001%. No – there are times for machines and times for the grasping and pummelling of human flesh by human beings.

The Economist article started off with a smug summing up: “No wonder” it read, “they are called ‘patients’. When people enter the health care systems of rich countries today, they know what they will get: prodding doctors, endless tests, baffling jargon, rising costs, and above all, long waits …” The Economist seems to find a problem with that.

So what’s their answer? You’ve guessed it: patients’ lack of knowledge and control.

Information is not knowledge, and knowledge is not education. It’s difficult to see how this digital health approach will benefit the majority of the population who are relatively computer illiterate and have difficulty even texting. I do recall several patients who are knowledgeable and in control, who searched the Internet for relevant clinical studies, asked good questions and did not consume an undue amount of time – and were a joy to care for. But these are the exceptions.

Our health care world today may be dividing into those few who are digitally adroit and those who labor long and hard to access Internet information or who cannot afford a computer or mobile phone. It may be asking too much of the majority of our patients. Digitization may be good for the wealthy and the elite, less so for the poor and digitally incapable.

Artificial Intelligence

One of the more obvious benefits of setting up artificial intelligence algorithms will be the rationalization of patient care rounds or tumor boards. Currently, decision making depends on who is present at rounds and the relative experience and knowledge of specialist attendees. Different courses of action are advised depending on representation from involved specialties.

By feeding in relevant clinical and disease details, an AI program should be able to cough out a multi-disciplinary plan based on input from the very latest clinical studies. The plan would then be assessed as reasonable or not and modified by staff clinicians depending on the patient’s clinical, financial and cultural circumstances.

A critical job of specialists then becomes determining which clinical studies are worthy of entering into the software. This implies that future specialist clinicians have real-world knowledge of clinical trial design, statistics and management. This approach would make decision making more fair, especially when a full deck of specialists is unavailable.

On the other hand, Alphabet is bringing out an AI program that claims to predict possible deaths of hospitalized patients two days earlier than current methods, thereby allowing doctors to intervene earlier and (one hopes) more successfully. It’s difficult to see how this approach will beat a fully functioning clinical team seeing and monitoring their patients regularly. And I’m uncertain that a flashing light beside a patient’s name telling you that Patient A’s respiration rate has increased, or that Patient B has a risk of DVT is going to be better than a fully aware clinical team, though it may be helpful if an inexperienced or short staffed team is on the ward. A program merely giving a flashing light on the screen for a patient in Cheyne-Stokes respiration, or for an expected death, is an unnecessary bit of over-dramatization.

Apps booking appointments

The prediction here is that booking an appointment for the digital cognoscenti will be just like booking a round of golf. This might work in a start-up practice that’s under-booked, but will be difficult for the majority of general and specialist practices and opens the door to unnecessary and over-frequent visits. It implies that demand for each clinician is the same and each visit is of equal duration – which is rarely the case.

The electronic medical record

Apple plans to make a new health app which will bring together health information from doctors’ offices, hospitals and data from the iPhone itself to give the individual control of their own health record and allow more time to spend gazing at the little oblong thing in his or her hand. This is, however, being planned on many levels including our own AHS with a “patient portal” – a system giving everyone access to their own health and illness information. It’s not hard to envisage a group of patients making good use of this but another group quite unable to handle the complex information permeating the untrained mind. The “worried well” group may well become really worried.

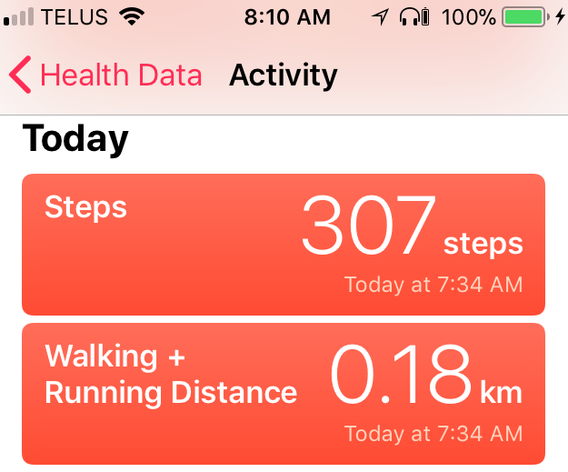

In-phone sensors will document cardiograms, glucose levels or whatever. Pattern recognition in dermatology should allow differential diagnoses and monitoring of spots and pimples. Patient selfies sent in to the attending surgeon of wound healing are already used.

Communication

The science of medicine and surgery is about diagnostics, therapeutics and knowledge of disease processes, but the art of medicine and surgery is about human contact, empathetic communication in the taking of a clinical history. It depends on the healing, comforting impact of a thorough, knowledgeable physical examination. The pedlars of Silicon Valley will never disrupt that, and it is just possible that having more data at the physician’s fingertips may improve communication. I do hope so. But this will not come cheap.

*rammie: A beautiful Scots word meaning a disorganized cluster of people clamoring for attention