The Saddle Lake First Nation community is proud of their record with keeping COVID-19 at bay. This tight-knit community of about 7,000 band members living on a reserve near St. Paul, Alberta, has experienced only one COVID case as of publication date of this issue of Alberta Doctors' Digest. They have achieved this by being proactive from the start.

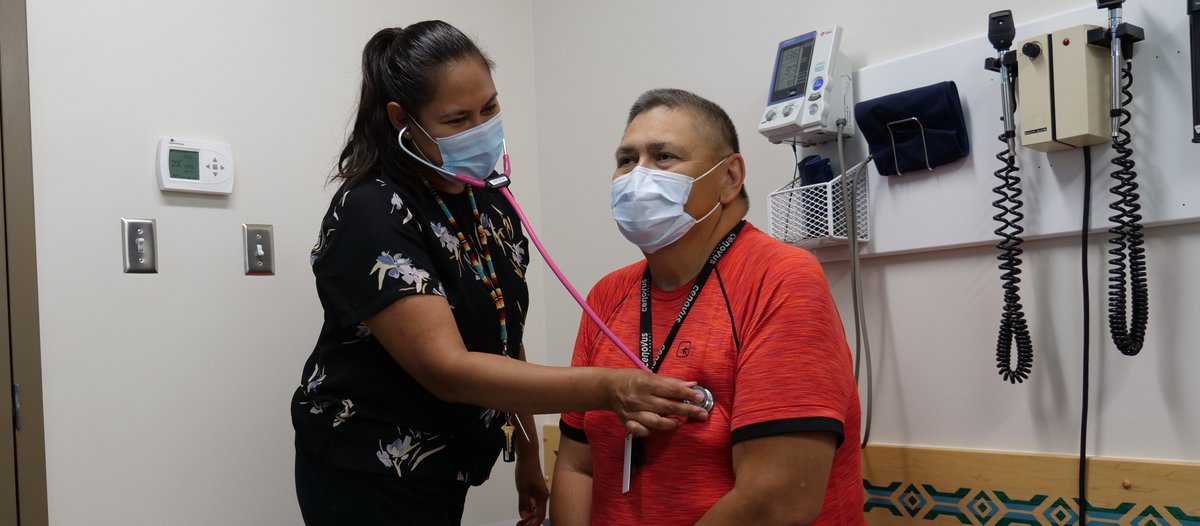

Dr. Nicole Cardinal is a physician practicing at the Saddle Lake Health Centre. She says the aspect of multi-generational social housing on reserve created the realization that they needed to act fast rather than waiting to be told what to do, whether from the federal or provincial governments.

“Our first goal was to keep the health centre open,” says Dr. Cardinal. “We knew the importance of accessing health care in our community is essential. We did not want to close the health centre and create a situation where our people would need to leave the community for care.”

“So we took steps to limit the number of people coming in to the health centre, and we triaged people according to AHS guidelines,” adds Dr. Cardinal.

She says the community also took the extra measure of restricting outside visitors coming into the community. Plus community members were discouraged from travelling away to high-risk cities and potentially bringing the infection back to Saddle Lake.

“Because we have so many social complexities in our community to take into consideration, we knew that if we had a COVID case in Saddle Lake, it would multiply because of the way Indigenous communities work,” she adds. “So we also ramped up testing at the health centre, including a drive-through test facility.”

Dr. Cardinal grew up in the community and is a band member practicing medicine at the local health centre. Because of her background, she realized there are aspects of Indigenous culture that needed to be respected in the fight against COVID. One aspect was that telemedicine would not likely be very successful because members of her community prefer to see their doctor in person. “A lot of our members don’t have cell phones, computers or Internet.”

As well, Dr. Cardinal says the number of community members who practice traditional Indigenous medicine has increased since the start of COVID. Although she practices Euro-Canadian medicine, she knows that having a strong respect for traditional approaches is essential.

“A lot of our community members feel traditional medicine is helping to control the rate of COVID in our community,” says Dr. Cardinal. “So I’m not going to discourage them. But I do want to work together with them. They need to feel they are in control of their health care, which they are. This is something they believe in culturally.”

“Participating in ceremonies are a form of medicine for us, such as participating in sweats, sun dances and prayers. When we had tighter COVID restrictions, it was quite difficult for our members to participate in these activities, and it was hard to suggest they should not do it..”

“Our community cares about each other because we all know each other,” concludes Dr. Cardinal.

Related story

COVID-19 and the decolonization of Indigenous public health

Editor’s Note: In future issues of Alberta Doctors’ Digest, look for expanded stories about Indigenous approaches to health and wellness, colonial legacies such as residential schools and Indian hospitals, and colonial social determinants of health.

Banner photo credit: Marvin Polis