Editor's Note:

In light of recent news about unmarked graves at Indian residential schools in Canada, Alberta Doctors' Digest is re-publishing the following story from our Special Issue on Indigenous Health.

Saddle Lake Cree Nation family physician, Dr. Nicole Cardinal, quietly contemplates the question of “What advice do you have for non-Indigenous physicians …” as they work to improve and develop successful relationships with their Indigenous patients?

“Indigenous health is such a complicated issue,” she says. But key and crucial to the relationship – explains this Indigenous physician who returned to her birthplace and home on Saddle Lake to practice family medicine, is trust. Trust built on a foundation of knowledge of Indigenous peoples and their communities and culture.

In order to successfully treat Indigenous patients you need to “be aware of Indigenous issues and that includes health,” Nicole advises, and develop an understanding of where they’re coming from in terms of trauma they may be experiencing and its effect on their mental health. The mental health aspects of health care are “often overlooked by family physicians,” Nicole notes. “We might not be as comfortable dealing with abuse or mental health issues.

“There are so many barriers to accessing health care (for Indigenous people), and if you don’t know or understand the issues you can’t properly treat an Indigenous patient.

Non-Indigenous doctors need to know what these barriers are, including barriers of service access and provision. “What health care services are available (on their reserve; in their home communities) and which aren’t?”

The shadow of residential school lays over many Indigenous patients. “I take more time with my Indigenous patients and I try to understand where they’re coming from,” says Nicole. “I ask them if they have a fear of the health care system. If so, why? Have they been to residential school? If they have, that explains a lot to me and helps me tailor my care.

“If they have a lot of traumatic experiences, whether residential school or having a higher-risk home where there was violence or addiction, alcohol use … then I know where they’re coming from. It helps me keep in mind mental health aspects of care.”

It comes down, or rises up, to trust and relationships

As a physician practicing medicine on the reserve, Nicole is quick to acknowledge the greater ease with which she can develop relationships with her Indigenous patients. “I get to know my patients, their families and their backgrounds.”

She also understands the trust- and relationship-building challenges that physicians in urban settings experience when treating Indigenous patients. “There are a lot of Indigenous patients seeking care and help in urban centers,” Nicole notes.

There is a common denominator, though, in successful Indigenous patient-doctor relationships, whether in rural or urban settings, and that is trust. “We have a very strong sense of community in our First Nation communities,” explains Nicole. “We’re very close to each other. We lean to our community members; to our family and friends.”

Nicole speaks from personal experience. When she first returned to her home of Saddle Lake to set up her practice, “patients were slow to warm up,” she says. “There was a history of doctors rotating through the clinic – coming and going. It took a year for my patients to feel comfortable and confident that I was going to stay.”

“Success with Indigenous patients will come from investing in the relationships,” Nicole explains. “A sense of abandonment affects a lot of Indigenous patients. If they think you aren’t invested, they may leave. They won’t be fully in the physician-patient relationship,” she explains.

A holistic health approach… Understanding the impact of colonization and residential school on the First Peoples

“I bring physicians back to the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action,” says Nicole. “One of the Calls to Action (Health - #18 to #24) is for our medical system and practitioners to be aware of Aboriginal issues and that includes health.

“I would like to see more physicians becoming more knowledgeable about Indigenous people and their communities,” she adds. “Developing that knowledge comes from studying and making a concerted effort to learn, but it also comes from talking with your Indigenous patients, asking thoughtful questions and again, knowing where they come from.

“If you don’t know that we don’t have access to physiotherapy, or that we don’t have a lab here, or that the medication you prescribe isn’t covered by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, then you’re left wondering, ‘Why isn’t my patient following through?’ This knowledge is critical to ensuring follow-up", she adds.

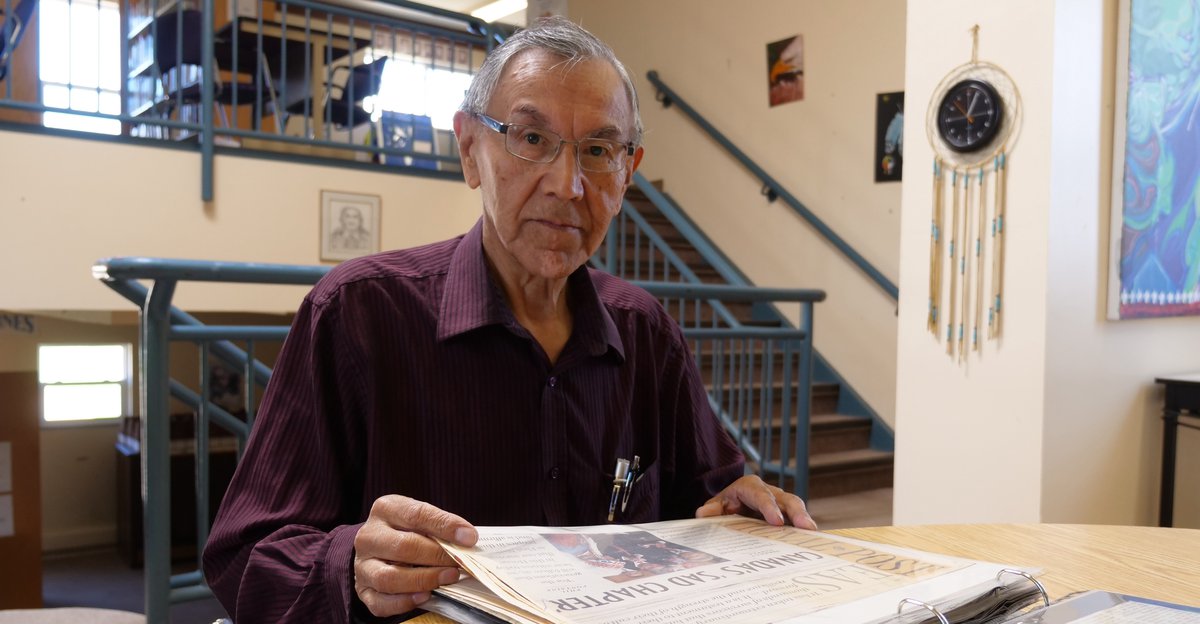

Former Saddle Lake Cree Nation Chief and Band Councillor, Eric Large, speaks to the effect the residential school experience can have on Indigenous people’s ability to trust and be open with non-Indigenous people, particularly those in positions of authority.

Eric resided at and attended Blue Quills Indian Residential School, just west of St. Paul, from grades 1 to 8 (1953-61). He continued to live at the school for the duration of grades 9 to 12 (1961-65) while commuting daily by bus to Racette School in St. Paul. Eric was seven when he arrived at Blue Quills, where he quickly learned that life there would be one of strict routine, constant prayer, unhealthy food and loneliness.

“It was very heartbreaking to go live there,” he recalls. “But we kind of got used to it, to the routine … up at 6:30 a.m., going to church on Sundays. Going to the classrooms from 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Going to meals … doing lots of praying – in the mornings, at mealtimes, after meals, at bedtimes.”

Family was never far from Eric’s mind; the absence of his immediate and extended family was painful. “We missed our parents, our grandparents, our aunties and uncles and relatives on the reservation.”

Eric’s older sister also attended Blue Quills but he only recalls “seeing her twice.” Boys and girls were kept separate, he explains, except in the classroom. If you had an older or younger sibling, you maybe saw each other at mealtimes, and even then, you were not allowed to speak to each other.

Along with the routines and prayers came constant oversight and control.

“Me and my fellow students were totally under the control of school administration, the male and female clergy,” says Eric. “We learned to keep quiet at school and in church. Only in the playground could we express ourselves. We got used to this supervision and constantly being watched.”

And while they became accustomed to the regimented supervision, Eric notes that in the long term, it led to: “a state of hyper-vigilance in later life. I saw it in myself and others.” After he graduated, Eric says he was: “wary of authority figures, like clergy, the divinity, government agents, bureaucrats, lawyers, judges, police … But not so much the medical community. I trust them – they’re trying to help us recover.” He added: “It’s the legal and political authorities that are more difficult to trust.”

“You should just get over it … move on … it was in the past …”

To the refrain of “get over it …” that Indigenous people frequently hear regarding the history of residential schools (the last residential school in Canada was closed in 1996) and the multi-generational, long-term effects of it, Nicole says you could add to that, “Government and church have apologized. Isn’t that enough?”

The answer is no, it is not. “The impacts of those actions affect us to this day,” says Nicole. “A lot of students who went to residential school are still alive today and dealing with what happened to them, and their experiences. They’re still on their journey to healing.

“For us, it doesn’t seem like it was long ago. We feel it today and see it in our children, our parents and grandparents. We’re seeing the fall-out,” she continues. “It’s an important moment in Canadian history that is still embedded in our culture today; in our attitudes and thoughts when we’re accessing health care … there are a lot of similarities (between) being in a residential school and accessing an institution such as health care and the hospitals.

“People in suits, touching patients without permission … It’s a lot harder to get over traumatic experiences,” Nicole observes. “For a whole family to be healed … we’re probably not going to see that for another couple of generations. (We’re still) developing the skills we need to heal past the effects of residential schools.”

What does change look like? To be treated with dignity; to close the gaps in health care disparities.

When asked how he would like to see things change, as part of reconciliation, Eric says, “I and my fellow citizens of Saddle Lake – my neighbors, friends and relatives – would like to be treated with dignity. To have it understood that we have a life, we have peaceful people.”

Acknowledging “a history of unlawful activities,” Eric says, “But that isn’t the majority of the people. Our people are kind. They’re just people, with feelings, with aspirations … to bring up children (and grandchildren) wisely. They wish to be doctors or nurses. And scientists and managerial people.

“Lo and behold … lawyers! And maybe judges!” he adds with a smile. “We’d like to enjoy the land, the water, the air … and the seasons, as they come.”

For Nicole, it comes back to the TRC’s Calls to Action. “I want to see actions taken to close the gap in health care disparities between First Nation and non-First Nation people. “This is the biggest one,” she says. “Because it affects our mortality; our life expectancy.

“We want the same thing as every other Canadian. We want access to health care. We want safe health care. We want health care professionals to understand where we’re coming from.”

The transformation of a residential school

In 1970, as the federal government was moving to close residential schools, including Blue Quills, the Indigenous communities of the Saddle Lake/Athabasca district formed a plan to take over management of the school; at the same time, taking the education of their own people back into their own hands.

After receiving approval from the federal government, Blue Quills School re-opened in 1971, focusing on an elementary and junior high school curriculum. The school expanded to include a high school curriculum and subsequently “developed into a post-secondary institution providing adults with degrees that embrace Indigenous culture at undergraduate, graduate, and doctorate levels, with some of the teaching taking place in the Cree language and with a curriculum that embraces both Indigenous wisdom and Western thought.”

In September 2015, Blue Quills First Nations College became University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills.

Banner photo credit: Marvin Polis